On the Immediacy of Objecthood and Situatedness of Architecture

/

LIU = Liu Yichun CHEN = Chen Yifeng

Shanghai 2016.11.16

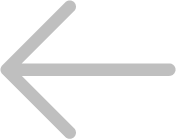

LIU: In 2013, we held our first solo exhibition at the Architectural Center of Colombia University in Beijing. The title of the exhibition was On the Immediacy of Objecthood and Situatedness of Architecture. The architectural critic Qing Feng wrote a commentary essay, Between Situatedness and Objecthood, on the exhibition, which was also a brief summary of Atelier Deshaus's practice. Two years later, as Qing Feng published his essays into a book, he asked us to write some thoughts on that article, and you proposed a new understanding of objecthood and situatedness. Perhaps we could first talk about that.

CHEN: I wouldn't say it's an entirely new understanding but rather a further reflection on our practice. For a very long time, we have focused on the creation of situatedness. How can we take a step further and push our practice from an aesthetic expression of picturesqueness and poetry toward something that is more fundamentally architecture? I guess the title of our 2013 exhibition, On the Immediacy of Objecthood and Situatedness of Architecture, summarizes such thoughts, that is to say that we hope to transcend situatedness by putting an emphasis on architectural materiality. And then, the question becomes: if this situatedness based on objecthood must go beyond formal beauty and perceptive pleasure, what are its possibilities?

LIU: As a matter of fact, our views at that time came from reflections on our own projects as well as architectural practice in general during that period. There was an emphasis on architectural narratives, including that of a building’s relationship with urban environment and society. An architectural ontology was of less concern and touching buildings were rare as an opportunist approach became attractive. So we proposed to shift our attention back to things in hope that architecture could still have its own solid ground in dealing with various social issues. It might appear to be an argument about architecture's interiority as a discipline and its extension with other disciplines. Yet such was not my intention. Both situatedness and objecthood are approaches through which we could deliver extraordinary design. In today's society and urban environment, architecture is no longer a pure discipline, and the keyword Situatedness/Objcthood, Situatedness/Objcthood, which we proposed for our 2013 exhibition indicated such a progressive relationship within its combination. Now, I'm more inclined to think of these two as juxtaposed. Every building is an outcome of the interplay between the two. And within this relationship, I think objecthood constitutes a crucial foundation and concerns more with architectural interiority.

CHEN: I think we could also understand objecthood as an ontological part of architecture, or as an autonomous part, and position situatedness as an extension of architecture. As you mentioned, I think that the focus on objecthood has highly practical meanings in contemporary Chinese context. However, in term of architecture, objecthood contains multiple layers of meanings. It could refer to the structural, material and constructional elements that are related to an architectural object. It could also be understood as the bodily experience of a self-conscious subject. It could even be considered as a kind of convergence in a more extensive sense, similar to Martin Heidegger's definition of things.

LIU: You have read quite a lot of Heidegger's writings in the past two years. For you, how does this understanding of things impact your design?

CHEN: In Heidegger's late writings, he discusses extensively about things. For him, a thing does not refer to the substance as a bearer of traits, or to the unity of a manifold of sensations, or as a formed matter. What makes a thing a thing is its usefulness. Compared with mere-things or things-in-themselves, what Heidegger defines as a thing is more similar to equipment. However, for human beings, a thing’s usefulness does not necessarily indicate its instrumentality, but rather the convergence of meanings that come with its usefulness. From this perspective, we need to think about if architecture could be more than a mere shelter and if the being of architecture is to seek meanings.

LIU: Heidegger says that the void of a pot is for the containing and pouring of water. Pouring water is an act of giving, which is the true purpose that completes the meaning of the pot as a thing. For Heidegger, the definition implies the being of fourfold - the sky, the earth, mortals and divinities. The fact that nothing is in an isolated state is also of special significance to architecture. I think there's a problem of priorities here. Perhaps, what you referred to as "a convergence of meanings" could be understood as situatedness, which is a higher goal and comes after the need for sheltering. When an architect designs a specific building, the creation of objecthood comes first and how to response to the situatedness is an intentional act during the process. What I'm interested now are two approaches. One is inside-out. For example, I'm interested in how the regularity of a thing and its structure could be adapted to the needs of program and context as well as could construct itself. Another is outside-in, such as how to understand context and how to create meanings within both physical and social context and express them in the back-and-forth thing-making process.

CHEN: While philosophical discussion helps us to discriminate direction and make grand value judgments, it could hardly be directly applied to specific projects. In respect to practice, you mentioned two approaches of thing-making. I think the later outside-in approach is very clear to understand and is what I also maintain. Yet I have questions about the first approach. How would an architect act in a circumstance in which the regularity of a thing is not evident and cannot answer to exterior needs, or could even hardly guarantee its own being? We still take structure as an example. Most buildings in China now are of a generic frame structure whose wide application legitimizes its being. In most cases, it meets programmatic needs and could be adapted to fit its context. Could we also say that such a generic frame structure also construct itself? The frame structure has its own regularity, but does this regularity also inspire an architect's creation?

LIU: I believe that there's an internal regularity that could be mirrored through or triggered by external needs. Of course, it is related to our accustomed ways of thinking. In architectural design, such could be a choice, a method, or a technique. Perhaps regularity is not the most accurate word. By regularity, what I attempt to refer to is a kind of interiority of which structure is one category. The reason that I want to bring this up today is that, first of all, I think there are great opportunities in it and secondly, it is also an aspect that lacks well-focused consideration and expression in our past practice. If a frame structure could produce a relationship with program, space and its site, I think it could also contribute to a different architectural interiority. For me, structural element is essential to architecture as it is something that makes a building stand. If we review architectural history, we could find a number of discussions about its exact significance. However, despite its historical importance, there are fewer discussions about it compared with that on urban environment and society today.

CHEN: As an ontological part of architecture, structure is how architecture withstands gravity and other natural forces in a state of self-sustaining. Structure is also a crucial carrier of architectural materiality, which condition is quite self-evident. Yet in terms of expressing structure in design, I think it needs to be represented more than just shaking off its generic state. If we remove the central column in Kazuo Shinohara's White House, the soul of the building is also stripped away. In this case, structure or structural element has transcends materiality.

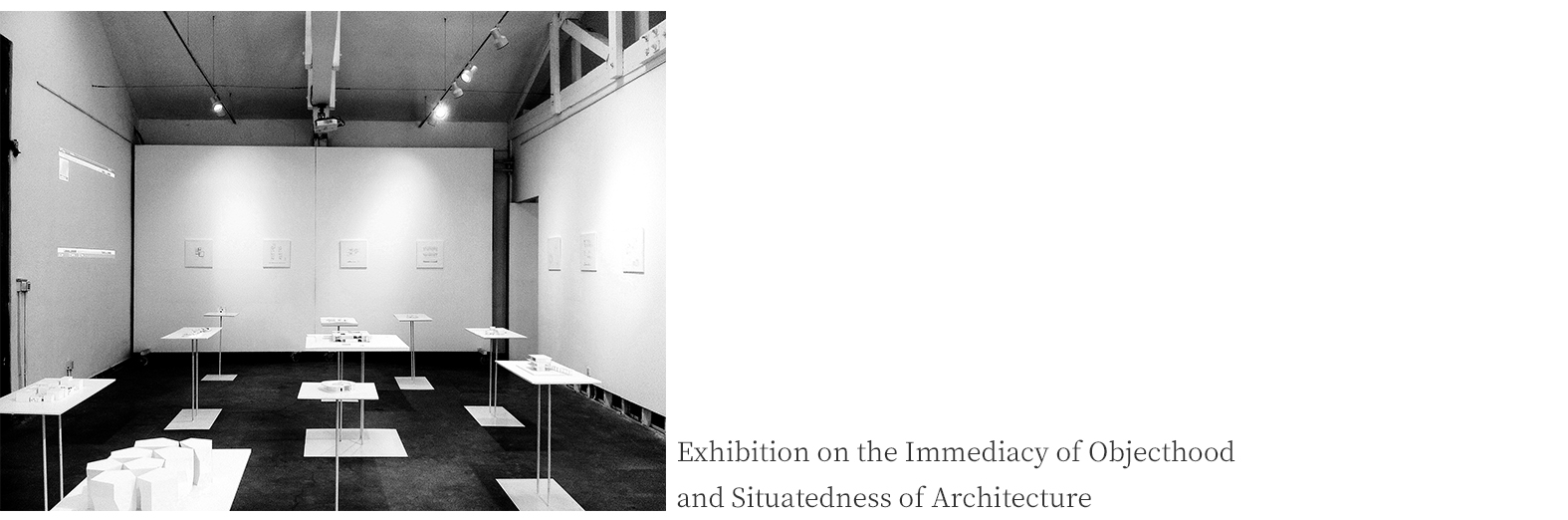

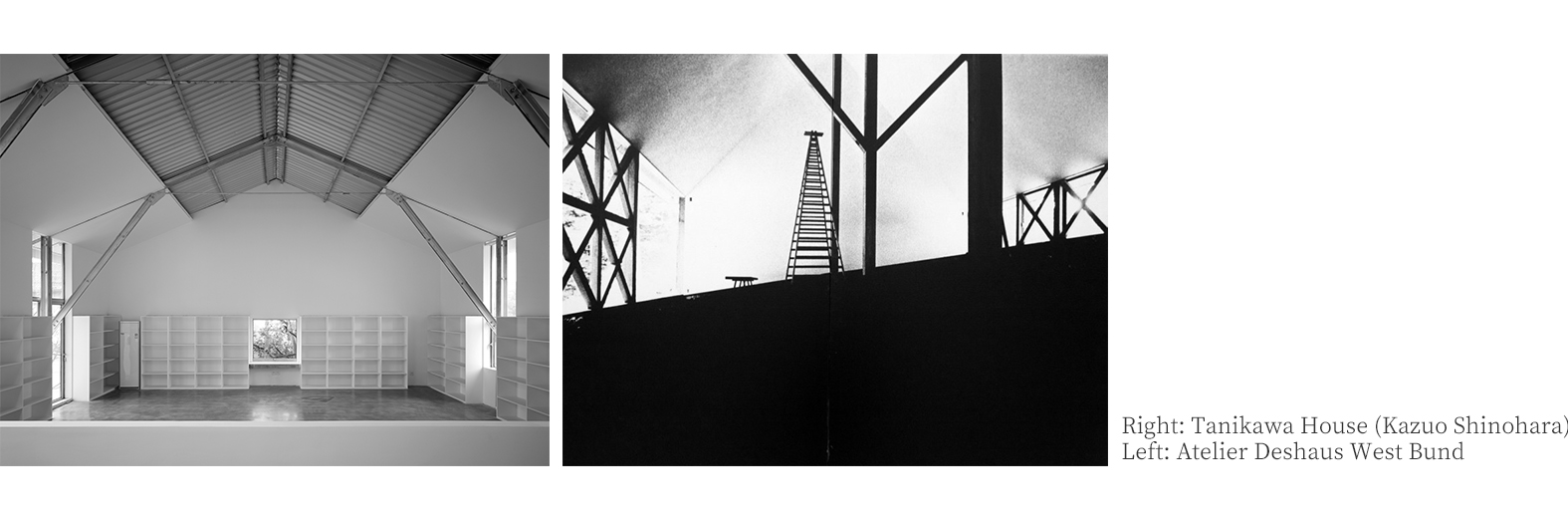

LIU: You used the word generic twice to describe structure and in my understanding, what you referred to is a sense of neutralization. In other words, structure, which makes architecture stand, is in itself neutral and does not carry any cultural meanings. However, an element with zero-degree meaning hardly exists in architectural history. The central column in Shinohara's White House is the outcome of thingness when he attempted to eliminate the meaning of the central column in traditional Japanese wood frame architecture. In contrast to what you referred to as "shaking off its generic state", it completes a transcendence as its original meaning is stripped away. In any case, I'm greatly intrigued by the concept of thingness, which operates around the ontology of architectural materiality despite its mannerism-like method. If we go back to the two approaches of inside-out and outside-in, we could find a connection to two books that Prof. Wang Junyang mentions in his essay What Is Theory? . One book is Leon Battista Alberti's De Architectura and the other is a mythical book, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, whose author is still unknown. Wang Junyang proposes to regard two books as representatives of rational and sensational thinking on architecture. This reminds me of the title of A+U(0903)'s special edition on Atelier Deshaus, Fusion of Pertinent Emotion and Reason, which also covers these two aspects. From De Architectura to Viollet le Duc's structural rationalism, from Peter Eisenman's disciplinary autonomy through formal studies to Kenneth Frampton's Studies in Tectonic Culture, architectural ontology is the main concern of these theories. In Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, however, the border of architecture as a discipline is largely extended by divorcing from the ontology. In particular, Wang Junyang argues that for architecture of the 20th century and especially contemporary architecture, city has to a more and more great extent replaced body to be an abundant resource to expand disciplinary border. As structure is an architectural element that withstands gravity and other natural forces, its coming-into-being reflects our bodily perception, and its cultural content that develops along architectural history is also closely tied to our bodies. From this perspective, the concern about structure seems rather against the wind and is less progressive as urban issues have been architects' politically correct concern. This puzzled me for a time. When we were having a conversation with a young architect, Zhao Yang, he said that architectural ontology no longer existed anymore. I was rather astonished at that time. Later, it came to me that both concerns were not mutually exclusive, for anyone, even someone who is not an architect, should have one's own way to express them. When such concerns are reflected in architectural design, they would naturally transform into strength of architecture. The final expressive form is based on the choice of the architect and as such, structure also plays a role in urban issues. Our new office in the West Bund responds to such issues as space, site and the temporality of urban regeneration with two types of structural forms: masonry and light steel. In my proposal for Pudong Gallery competition, I attempted to respond to urban and architectural scale with two different structural scales. Even though we did not win the competition, the idea is worth exploring in our future projects.

CHEN: In my view, the word generic refers more to a state of absence instead of a lack of cultural meaning. According to Shinohara’s description of the White House, the decision to conceal the roof structure and to stress the central column comes from an intention to abstract traditional Japanese space. Leaving aside the argument of whether the so-called thingness or objectivism that precludes cultural meaning is Shinohara's original intention, what is interesting here is that the concealment of the roof structure renders the central column standing out in a universal sense beyond the cultural level. Perhaps that's why Shinohara emphasizes abstraction in the project. As to whether to start from architectural ontology or its extension in design, it seems that while we could make a clear demarcation in a theoretical discussion, for practicing architects, it's just about putting extra emphasis on either of them. The same goes to that we could not completely separate sensational and rational thinking in our design process.

LIU:The White House is Shinohara's transitional project. As you have pointed out, the concealment of the roof structure makes the central column standing out, however, the spatial offset of the column deprived its meaning as the central column. I think that when Shinohara designed this project, the concept of thingness did not yet emerge and most discussions about the project were around abstractness. Yet, I think the project pioneered for his later ones toward objectivism. The Tanigawa House built in 1974 is a paradigmatic project of the beauty of thingness. I have visited some of his works, as well some of his apprentice Kazunari Sakamoto's projects, and I think that they're both architects that attempt to resist urban and social impact with a language that is ontologically architecture. For me, I think there's formless strength in such resistance and they develop an alternative response to urban and social issues. Speaking of which, what's your attitude toward contemporary condition in architectural practice?

CHEN: I agree with you. As you mentioned earlier, city has more and more replaced body as resources for contemporary architecture to expand its own border. It is such tendency that alienates contemporary architecture and human beings in a concrete sense. No matter how society develops, for a very long time in the future, the historical biological nature of human beings will still exist. As individuals, human beings' sensational reaction to such environmental phenomenon as light and dark, open and close, cold and warm, coarse and smooth, are still rooted in the collective unconsciousness that dates back to the ancient age. Moreover, human beings seek meanings as a consequence of their autonomous awareness. Spiritual quality does not necessarily exist in a building that perfectly meets programmatic, technological, economic and urban needs. According to the Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa, architecture's task is not to glorify or to humanize our everyday world, but to open a second dimension in our consciousness, one that is a reality of dreams, images and memories. So I think that the concern for body and people has positive meanings within contemporary social and urban background.

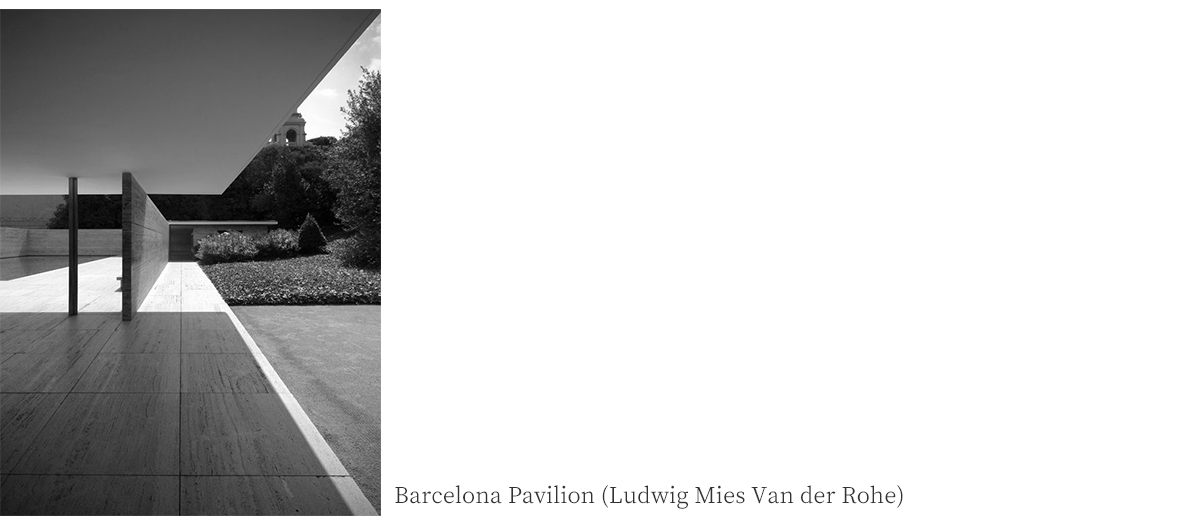

LIU: So generally speaking, both of us are looking backward, which is, of course, not a bad thing, for from a different perspective, looking backward is also a way of looking forward. Yet no matter at what position that an architect stands, the most difficult task is to materialize this position with an architectural formal language. Our early works attempts to interpret our understanding of traditional space of Jiangnan with abstract means, which is a concrete way of expressing our position. In Dr. Zou Hui's essay, Art of Memory, which is published in the special issue on Atelier Deshaus’s work of A+U in 2009, he pointed the phenomenological tendency in our design. What he describes as interplay of sensation and situation and the "search for the new understanding of reason (li) which does not cut off its relationship with the traditional philia of poetics and ethics (qing)" is very inspiring. He gives two examples from Western modern architecture which perfectly represents the interplay of reason and sensation: one is Mies Van Der Rohe's German Pavilion in Barcelona, the other is the analytical philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein's house in Vienna. Mies’ minimalist abstraction and Wittgenstein’s conscientious measuring demonstrate the extreme rationalization of space creation. In both cases, the consciousness of humanity is not lost but rather developed through careful consideration of physical details. In retrospect, though we have made many progresses in the consideration and articulation of details, it's still far from ideal.

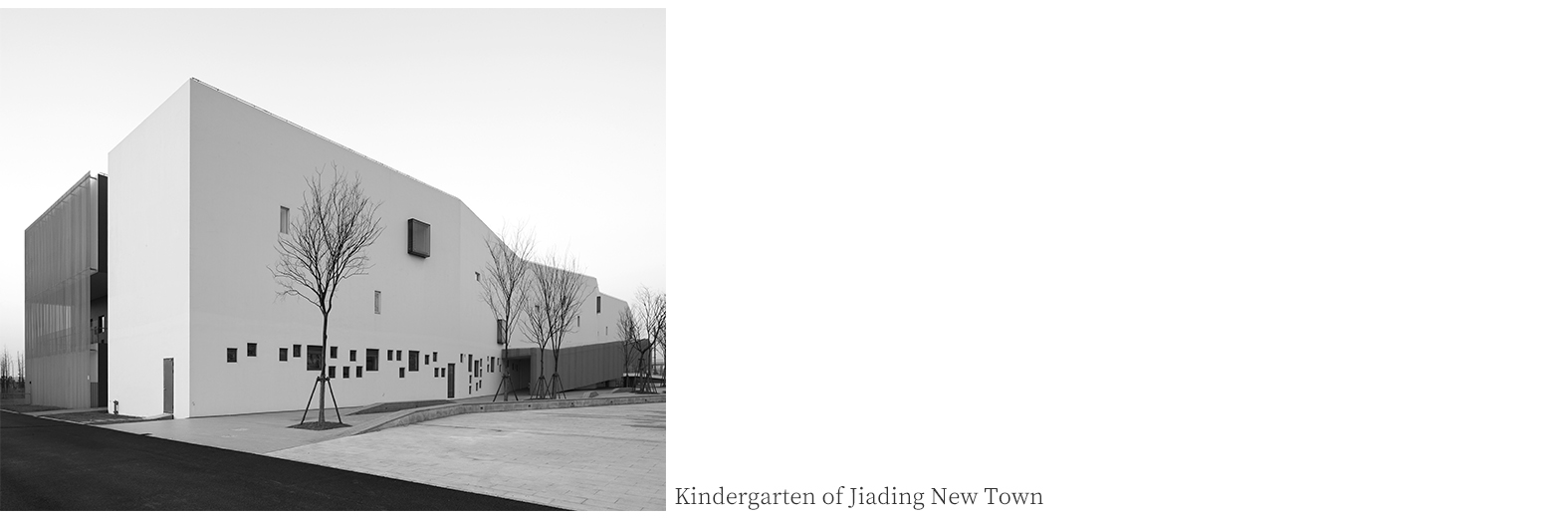

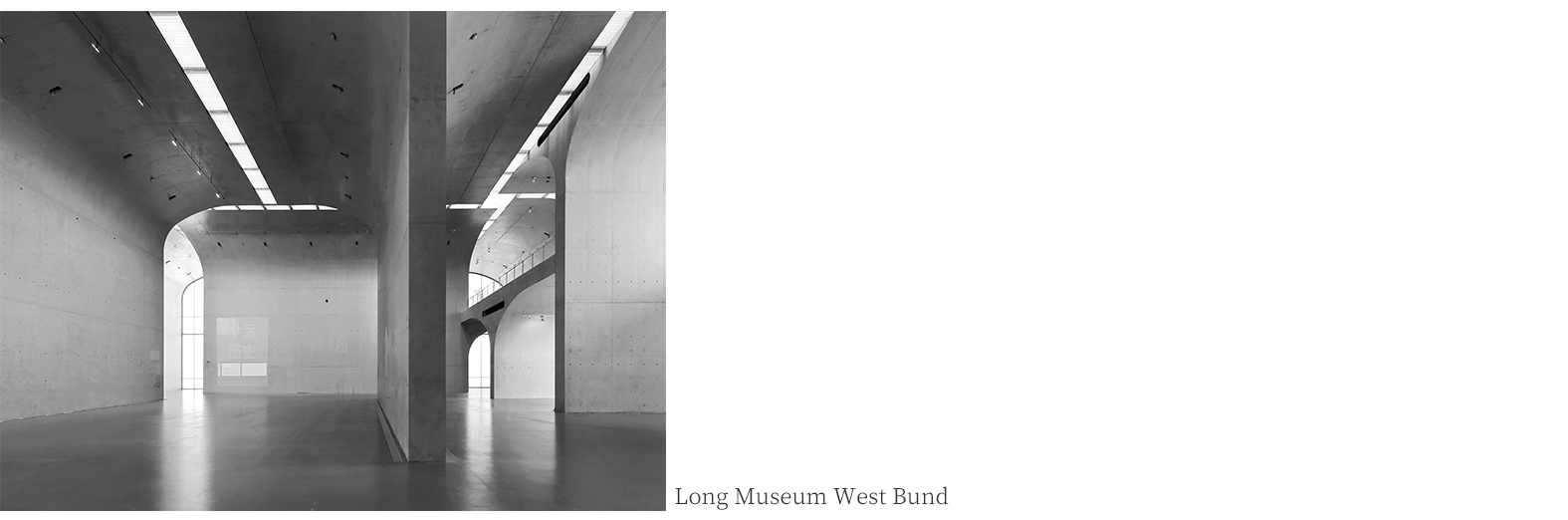

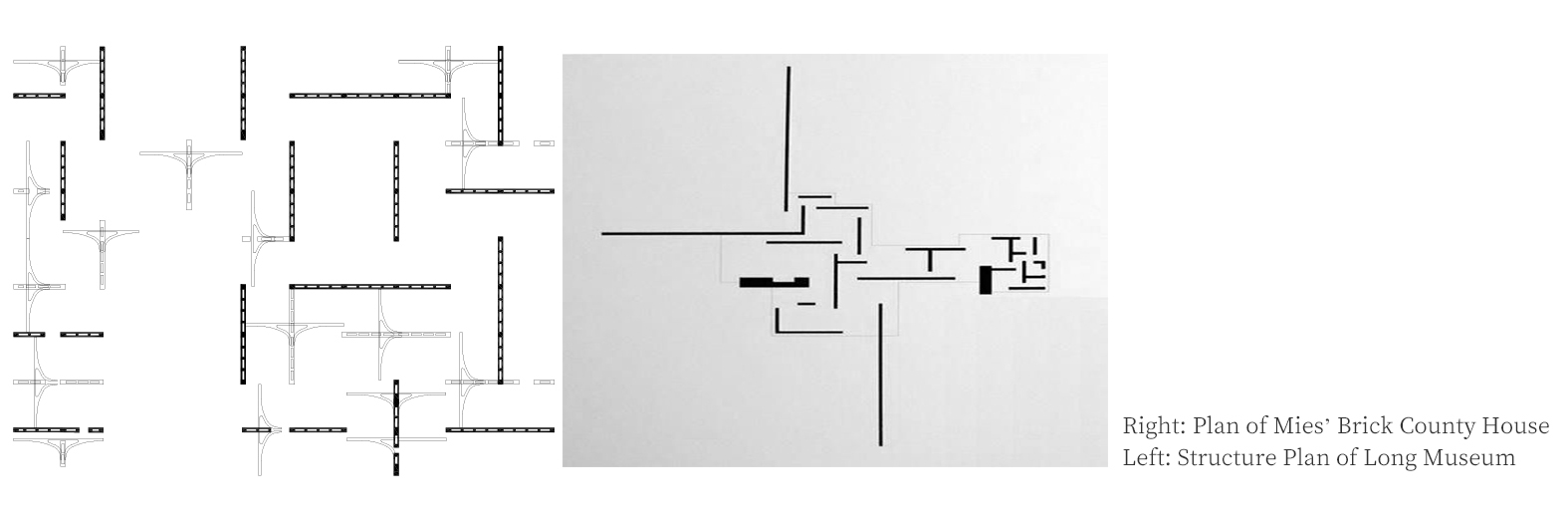

In the Long Museum West Bund built in 2014, a plan composition that is similar to that of the Barcelona Pavilion and the Brick Country House are designed. But when dispersed vertical walls transform into arch shapes covering a kind of space that is more directly related to human bodies, these spatial units' internal logic based on reason in turn constrains the position of walls. We went to great length to the positioning and the articulation of the project. I think your treatment with polylines is also an articulation. From the early Jiading New Town Kindergarten to the recent Huaxin Sharing Center, a connection could be observed with your interest in uncertainty and the treatment of polylines in architecture. What's your view on this?

CHEN: Looking backward, or rather looking inward, is a way to cope with present and as you have said, it's also a way of looking forward. I'm interested in the theory of place. Borrowing Heidegger's concept of dwelling, a place is something that is separated from the vast time-space. It is within the dwelling that the sky becomes sky, the earth becomes earth, divinities become divine, and mortals become mortal. Today, the study on place does not indicate a return to the Heideggerian farmer's house in the deep forest or a return to a pre-modern world. Just as Theodor Adorno has concluded, dwelling in its true meaning is no longer possible in today's condition and we are all clear about that. Even so, can an architect respond to contemporary condition through a kind of new place and experience? The uncertainty that you mentioned earlier is an attempt that I made in this direction. From a traditional point of view, the more defined the constituting elements of a place such as border, path, center, and etc are, the stronger the sense of place is. What I'm trying to do is to weaken it in an appropriate amount so as to shape a new sense of place that is ambiguous, multi-defined, and even disorderly so as to respond to society's multiple requirements on architecture and to make the place itself integrated into the ever-changing urban environment.

LIU: You wrote an article, Weak Order, in 2009, which is also related to uncertainty. Are there any differences in your understandings today compared with then?

CHEN: Weak Order can be considered as a summary of our practice before 2009, during which period we attempted to re-present our thinking about traditional built environment of Jiang Nan and especially Chinese gardens in an abstract method in our design. Such an understanding is foremost of an aesthetic level. Thus our early projects could be viewed as a situational expression based on sensation and Xiayu Kindergarten is a good example. Later on, we proposed such concepts as detachment, juxtaposition and etc to rationalize and summarize our practice and Weak Order was the outcome of that period. In the essay, I argue that by weakening the order of multiple elements that constitute an integral whole and obscuring their logical relations, a contemporary environment bearing traditional Chinese aesthetics could be created. Weak order leads to a relational uncertainty between elements. Uncertainty should also be a direction when we explore new place and experience today. Yet, here, uncertainty refers more to the state of each element itself. In the case of Huaxin Sharing center, while a wall is typically located at the ground and strongly defines a place as its border, the enclosing wall in this project is up in the air. Such decision comes from a consideration of both inside and outside condition. And as the enclosing wall floats, its state becomes uncertain and its definition of the site weakens. For the site and its surroundings, it creates an ambiguous atmosphere and relieves their contradictions, and for the site alone, it results in a tension that avoids an excessive loose state resulted from the weakened definition.

LIU: I think in our previous projects, we put much emphasis on aesthetics in general. Most of our early works are located in suburbs, whose characters are hard to grasp as their future context is unpredictable. So our spatial creation of a place is mostly within an autonomous interior. If a common order can be created in relation to the context, more strength could emerge from that. Huaxin Sharing Center is just such a case, in which a tension appears in a tight environment. I think that constructing a new place and experience is a task that every good architect should complete, and it could be done in a phenomenological way, or from an anthropological perspective, or with a very personalized method. I believe that there will be more approaches in the future.

CHEN: If we discuss architecture in respect to place, we consider it fundamentally as a thing. For a very long time, the abundant meanings of things are veiled as people regard them as only tools and thus to unveil meanings is just what we need to achieve through design. An emphasis on things is also an emphasis on architectural ontology, and its purpose has been discussed in details earlier. Here, I would like to quote from the Dutch architect Aldo Van Eyck to reiterate this purpose and also to conclude our conversation today: "What architecture has to do is no more or less than guiding people home."

/