Embodied Localness

/

Good old Jiangnan,

How well did I use to know its sceneries!

Sunrise on the Yangtze sets the flowers on fire.

But the springtime Yangtze turns a shade of indigo.

How can I not reminisce about Jiangnan?

The verb 'reminisce' broaches a sense of detachment between self and object. Perhaps the Jiangnan is even drifting further away from us.

As we find ourselves located in Jiangnan, where Atelier Deshaus' architectural practice is focussed. Many locations in the Jiangnan area have changed beyond recognition. They are more likely to remain as the settings of some of Lu Xun's works: village ritual performances, Runtu the childhood mate, Garden of a Hundred Plants, Three-Flavour Study, Kong Yiji and his aniseed-flavoured fava beans…or the well-known lines from Song lyrics or Tang poetry, 'the bright moonlit nights over the twenty-four bridges', 'How many terraces and towers are immersed in the light rain'. Or even like the Jiangnan sentiment that haunts Dai Wangshu's poem, 'with an oil paper umbrella, alone / I wander in the long, long / and lonesome, rainy alley, hoping / I will meet a girl / as melancholic as the clove flower.'

Although we constantly find ourselves in Jiangnan, but the real Jiangnan remains the one that haunts us from within.

Border

/

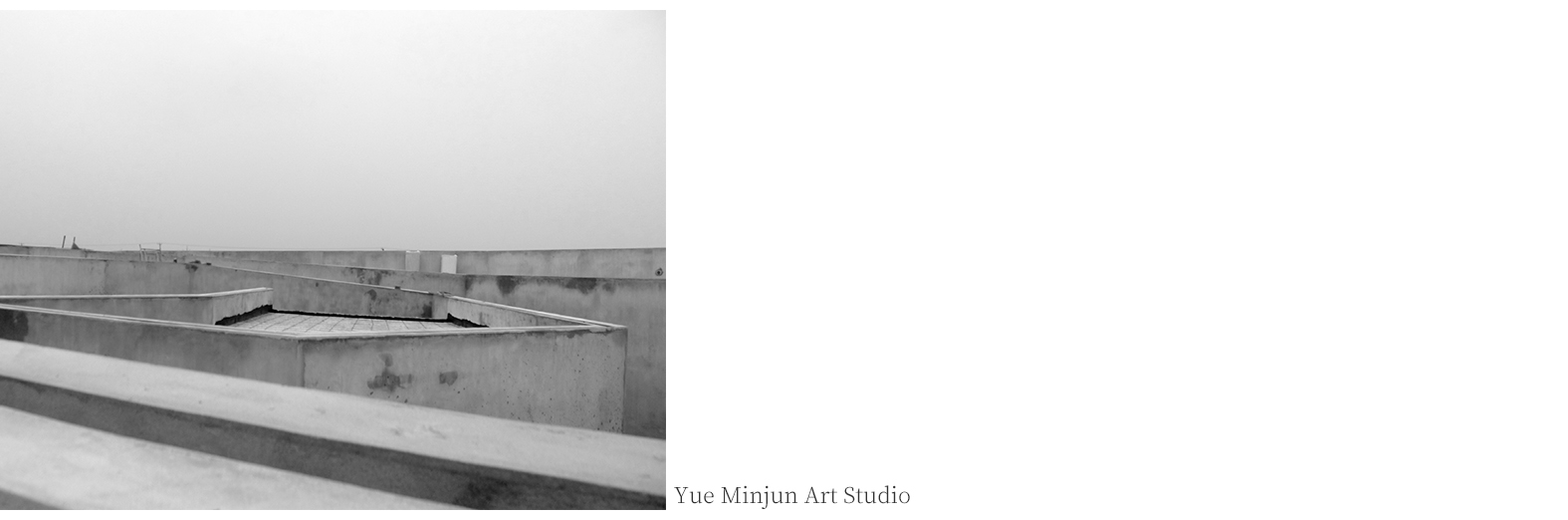

Without a question, the locale called Jiangnan is still a place filled with lyrical wonder and picturesque scenes. Her natural sceneries, vernacular houses and gardens have over the years held the gaze of many a visitor. The traditional garden is discussed the most often, although no conclusion is forthcoming. Discussions about it can continue for ever. At the beginning stage of designing the Summer Rain Kindergarten in Qingpu, Shanghai, we had heated discussions about the traditional garden. The focus most often fell on the path. Two curvaceous walls of the kindergarten initially followed the intuitive reflex of softly intervening on the site, and the inward feature constituted by this plan was also consciously contrasted with the traditional garden in the design notes of the time. Later we ascribed this to the concept of 'border'. At the beginning stage of our design, when faced with a suburban site surrounded with wild growths of grass, constructing a secure border and creating a centrifugal micro-environment within such border, seemed to us to be the most immediately recognisable strategy, which was also in line with our traditional view on the spatial environs.

The Jiangnan garden comes necessarily with walls, whether in a rural or urban setting. Naturally this has to do with the artificial borders between lands, and a natural corollary to this is the fact that walls precede gardens and courtyards. The Chinese concept of 'unity between heaven and man' takes place in a walled courtyard, and the walls serve as a 'border'. Mr Han Pao-teh has a theory about 'the contour as the focal point', which he used to explain the jade culture of China. According to this theory, Chinese jade carving would first achieve a contour before proper design even starts. Within this contour, shapes are created with the concept of cutting out the physical object, as emptiness and existence are interdependent and mutually supplementary. What jade carving and garden building have in common is the development of the unique raison d'être derived from the premise of a contour. As far as the traditional garden is concerned, what is related to the contour or border is the inwardness that is produced in the process. Its relationship with its surroundings is almost interrupted, due to the existence of the 'border', and occasionally 'scenes' are 'borrowed' to break through the 'border', thereby creating the most intriguing part of the architecture. The outstanding, colourful box-shaped volume of Summer Rain Kindergarten is precisely a kind of 'breakthrough' of the border.

In fact, if we temporarily put aside the political relations between urbanisation and the peasantry in China, the process of urbanisation itself, seen from a physical perspective, is one characterised by establishing borders. 'Borders' such as the courtyard wall evoke in us a sense of being within them, a primitive territoriality, which guides the building activities to turn inward. Yet, as the city takes its shape, modern life would prompt us to perceive the external beyond the borders every now and again. Thus, in our design, establishing borders implies stipulating the possibility of going beyond them. This perhaps best sums up the situation we find ourselves in: how do we identify and present values from existing living conditions? This is the opportunity we can seize.

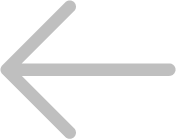

The Qingpu Private Enterprise Association Office Building, just across the river from Summer Rain Kindergarten, offers a powerful interpretation of the concept of 'the border' with a three-storey high wall made of glass. Its purpose is simple: we would like to build a pure, individual entity with clearly defined borders while making it open to the greenery. Just as the curvaceous, substantial wall of the Summer Rain Kindergarten, the three-storey high glass wall serves not simply as a wall, but also part of the external wall of the building. It establishes a border yet expects it to be dissolved or transcended. In some designs ever since, such as the Office Building on Plot 6 of Jishan Software Park, Nanjing, Qingpu Hydrological Station, Artist Village in Dayu Village, Malu, Jiading, Yue Minjun's Studio, etc., we have adopted the approach of shaping the architecture by way of the border established by the 'wall', which has no doubt undermined the importance of the element of 'elevation' in our design. In the meantime, we have produced a very strong inwardness, sometimes out of sheer lack of alternative, justified by the conditions of the time and locale. However, we hope that this inwardness is a point of departure rather than an end.

Li (Detach)

/

In 'First Explorations in the Crucial Issues in the History of Chinese Aesthetics', Zong Baihua suggests that the aesthetic value of li (detachment) is a research question in the history of Chinese aesthetics worthy of our attention. This has kindled our enormous interest in the subject. His discussion about li was mostly based on the hexagram of li in the Book of Changes. Despite the existence of various schools of interpretation of the Book of Changes, there is largely a consensus on the interpretation of the hexagram of li, which entails four layers of meaning: First, attachment (mutually dependent yet not detached), second, the cycle of detachment and attachment, third, brightness, and fourth, disarray. The character li implies being attached to. According to the tuanzhuan to li, 'The sun and moon have their place in the sky. All the grains, grass, and trees have their place on the earth.' (James Legge's translation). Apparently this is the ancient's attempt to understand the laws of nature. Suppose we find a small courtyard beautiful in spring. Its beauty may not come from the courtyard itself, as it may be attached to the trees in the courtyard, and to the warm springtime sun that casts a shadow of the trees in the ground. Perhaps we can say that the beauty lies in the architecture (the courtyard)'s relation with its surroundings, on which its beauty is hinged, just as Bai Juyi's immortal line 'Those lonesome grasses in the wilderness' has to enter into a relation with 'the spring breezes grants their new birth' before fulfilling its aesthetic impression.

Li is an understanding of the beauty that exists between objects in nature. This has helped us produce a clearer understanding of the form and overall relationship of architecture. Architectural beauty can be expressed by means of relations, such as 'attachment', which suggests to us its inextricability from its environs. Or the 'cycle of detachment and attachment', which attracts our attention to the formal characteristics of architectural groups. Architectural beauty can be more than a simple elevation, as it can also be based on relational expression. The Summer Rain Kindergarten is dissolved into the trees on the site and forms a holistic environment. Seen from the elevated highway not far from it, compound relations have formed between the dissolved, disparate units, between the trees, as well as between the trees and the units. Circulating back and form in the building, the upper group of bedrooms present another relation with the lower group of courtyards, and the final architectural form is the sum total of such relationships.

Perhaps since most of our projects have to do with nature or the wilderness, we have always unconsciously tried to reflect on better ways of incorporating architecture into nature and focus our design on establishing the relation between architecture and its surroundings. Yet this also gives rise to other issues. As we are confronted with the process of drastic urbanisation, the surroundings are always unknown. Even if there is planning, it is always subject to unpredictable and constant change. Eventually we have to resort to our own totality. So we will always intentionally organise architecture in relation to the natural environment, and more importantly, dissect and reorganise the building's components due to presumed functions, thereby focussing the design on the interrelationships between the dissected units. This has become our usual approach when faced with such circumstances.

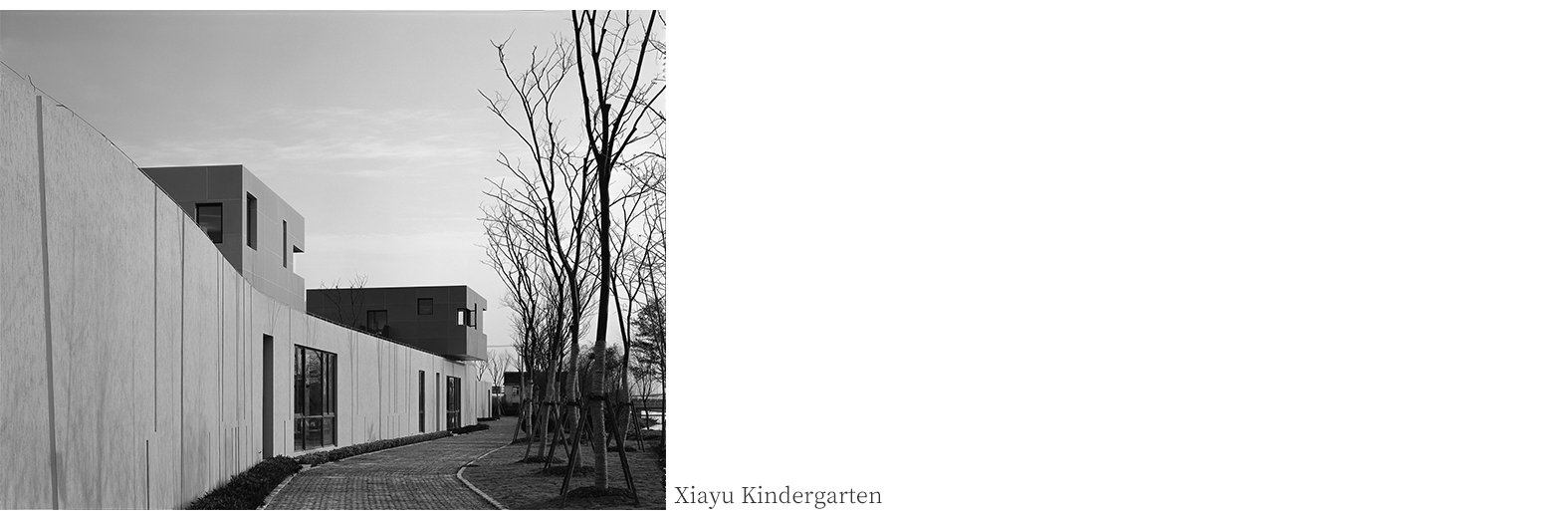

The design of Qingpu Youth Centre has been executed by dissecting the different functional spaces into units of relatively smaller dimensions according to the characteristic uses of the architecture. Then they are organised together by way of external spatial types such as courtyard, square and alleys. Youth activities within the building – the connections between different functional spaces and mindless loitering and serendipities – just like movements in a small city, are also our responses to the increasingly magnified urban dimensions in the urbanisation process of the suburbs. We hope that under the circumstances of magnified urban architectural dimensions, we can create humanised internal public spaces of smaller dimensions in an attempt to recreate the dimensional memories of the traditional town. Actually the detachment of these two dimensions is no longer an aesthetic issue alone. It has a direct bearing on our future living environment.

Juxtaposition

/

Juxtaposition is a way of constructing relations.

Juxtaposition has been widely used in traditional Chinese poetry, painting, and music. Wai-lim Yip has talked about the indeterminately juxtaposing relations of classical wenyan (literary language) poetry. Such as the well-known lines from the genre of the Lyric, 'Rooster crowing, hostel with a thatched roof, the moon', and 'ancient passageway, west wind, emaciated horse', in which the poet has not imposed a spatial relationship on 'hostel with a thatched roof' and 'the moon', or a temporal relationship between 'west wind' and 'emaciated horse'. Such flexibility has led to a simple relationship of juxtaposition, enabling phenomena or events to unravel naturally without losing any of their multiple spatial and temporal expansiveness, thus allowing us free movement within them for aesthetic values on different levels. In his Eight Treatises on the Transformed State, Dong Ganyu also observes that such a relationship of juxtaposition has allowed free space for the spatial organisation of Chinese literati's gardens.

Li is one hexagram in the Book of Changes. The relationship of juxtaposition is an immediate reflection of the organisational structure of the hexagram. The 64 hexagrams (symbolising 64 natural phenomena and their corresponding human conditions) are composed by attaching the eight trigrams, Qian, Kun, Kan, Li, Gen, Dui, Xun and Zhen, corresponding to eight main elements (Heaven, Earth, Water, Fire, Mountain, Marsh, Wind and Thunder). The organisational structure of the attachment and detachment processes is overlapping juxtaposition, through which objects can form rich and intriguing dynamic permutations. This is a very simple rule, and proves very effective if used properly.

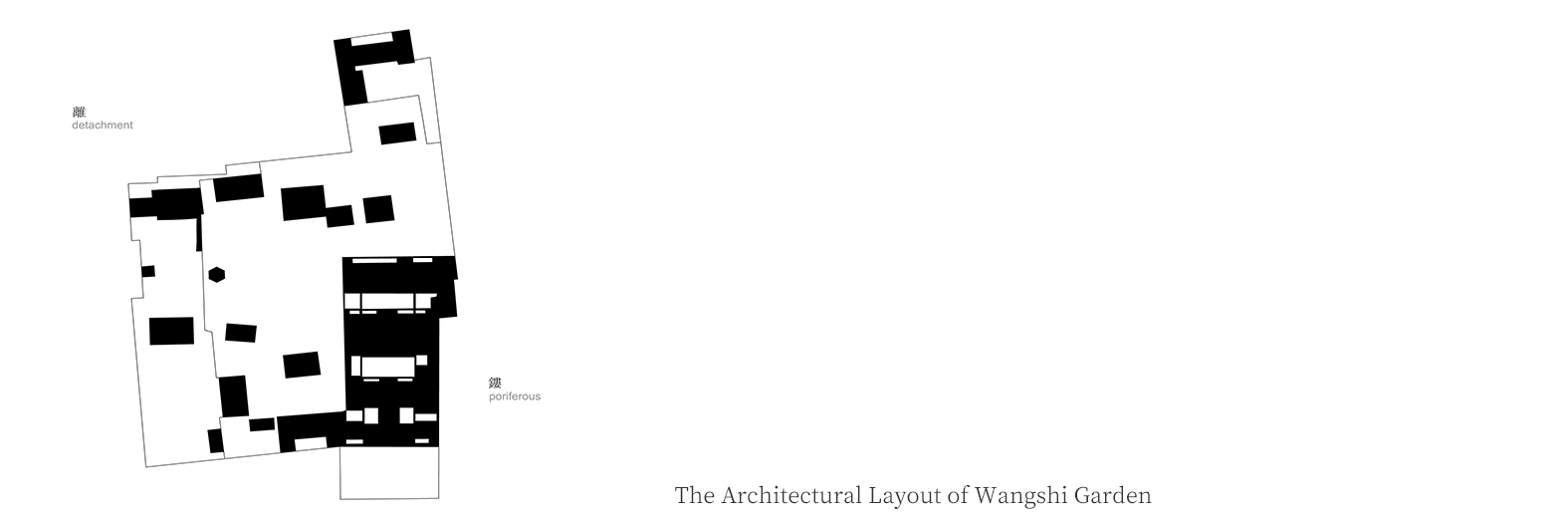

When we were analysing the architectural layout of the Garden of the Net Master in Suzhou, we discovered an interesting phenomenon, namely the fact that the buildings within the gardens and the residential courtyard exist in a relationship of reversible figure and ground. In terms of the presentation of its density, the buildings within the gardens have the least density and a free layout. But the residential part comes with a high density and a functional layout. In fact, the traditional garden and residential courtyard accompanied each other. The residential courtyard, laden with ethical values, would later develop a dense inwardness due to security concerns and construction models. As a relatively open, natural space, the garden can complement the courtyard and together they reach an organic equilibrium, which happens to illustrate a mutually complementary relationship of detachment and attachment.

Our understanding of the beauty of the detached and attached juxtaposition was first manifested in the Summer Rain Kindergarten designed by ourselves. The Kindergarten's Level 1 space is turned inward and without a view. Level 2 comes with a completely different scene, as the scattered little units are neither detached nor attached, linked up by the planks that drift at the rooftop, just like neighbouring villages. The vista was broadened, and the surrounding scenes present themselves in the frames formed by the gaps between the scattered little units, which prove to be the most moving part of the finished building in terms of spatial rhythm. Later we drew a figure-ground diagram for the Kindergarten in order to analyse the different densities of the two levels. The result was similar to the reversible figure-ground relationship of the gardens and residential courtyards of the Garden of the Net Master. Level 1 features a high density and comes with many small courtyards, and just as the residential courtyards, is 'inaccessible'; while level 2 features a low density, with architectural units organised in a detached yet attached way, and, just as the gardens, is 'open'. We have come to realise that the aesthetic impression of a space can come from a way of organising space that juxtaposes inaccessibility and openness. The charm of architecture can be produced in the processes of flux, change and aftertaste, which is perhaps due to the fact that human emotions have been channelled into it. In the design of Jiading New Town Kindergarten, we have intentionally enlarged the traffic space to form an independent 'non-physical' space full of ramps, and juxtaposed it with the 'physical' spaces overlapping with the closely arranged classrooms. This has created a kind of spatial contrast and rhythm, and enriched and enlivened the daily life of the children with imagination. The formal expression of the architecture can rely on the direct presentation of such a relationship of juxtaposition. Summer Rain Kindergarten features the overlapping of two distinctive levels, whereas Jiading New Town Kindergarten comprises the juxtaposition of two spatial volumes that are respectively 'non-physical' and 'physical'.

In most of the works by Deshaus, one can identify the impact of the above three keywords. Perhaps Summer Rain Kindergarten is the result of an unconscious effort. However, in the series that came after, this has become a conscious design approach. The Office Building on Plot 6 of Jishan Software Park, Nanjing also features a design that combines the detached small upper volume and the courtyard characterised by a fretwork underneath in an overlapping space. Jiading New Town Kindergarten comprises the juxtaposition of two spatial volumes that are respectively 'non-physical' and 'physical'. The Hotel on Plot E of Xixi Wetland is an extended, intertwined expanse of architecture and wetland growths. Qingpu Youth Centre is almost a small city with multi-layered external spaces of complex dimensions formed by attached and detached volumes. The Artist Village of Dayu Village, Jiading, is a cluster of many artist studios, each of which has clearly defined, inward courtyard borders. Within the courtyard there are even more closed studios with double-pitched roofs and cross shaped residential exhibition spaces that are open to the courtyard in all four directions. The P9 Office Building in the suburbs of Ordos City, Inner Mongolia, features the vertical overlapping of multi-density spaces, which, with the construction of 'fissure'-like spaces reminiscent of rockery, attempt to restore physical memories of men whose constitution is increasingly weakened in contemporary information society.

The recently finished Spiral Gallery within the Central Green of Jiading New Town is the most concentrated and most abstract expression of the three keywords. Its border is a closed loop of multi-arcs, enclosed by opaque coruscating perforated aluminium panels, which display alternatingly different kinds of inwardness in different weather conditions and at different times. In the 250 m2 building, two paths have been designed. One goes from the main entrance to the inner courtyard and leads first to the rooftop via the staircase, from closure to openness, takes a detour in the landscape of the Green, before entering the interior space, from openness back to closure. The other goes straight into the interior at the first opportunity available and takes a detour in the interior before entering the inner courtyard. The two paths can form a spiralling continuity, thus they exist in a relationship of juxtaposition. The surrounding scenery, thanks to the detour on the rooftop, also forms a detached and attached unity with the architecture (Figures 14, 15 and 16). The design of the Spiral Gallery has benefited from the reflections on spiralling images while we were working on Yue Minjun’s Studio within Dayu Village of Jiading. Here, the ‘spiral’ is but a form of intervention and furnishes no end. With the intervention of the geographic symbol of the ‘spiral’, we are able to create a sense of infinity within a limited border, which is also the characteristic of the maze. (Figures 17, 18). Hence we get to reconsider the characteristics of the 'wall'. Within a maze, 'walls' are not just simple isolators. They isolate yet keep things attached, which needs to be completed with our memories and emotions.

The design practice of the last decade has brought us to realise that we do not have to make a choice between tradition and the modern. Rather we should rethink or even redefine tradition and the modern based on our intellect and experience. We focus on locations and the past. Our designs may have started simply with nostalgia about particular locales and ended up with the hope that we can develop a kind of practice committed to abstractness and modernity based on accumulated experience of the locale in a society so hungry for change and novelty.

(by Liu Yichun & Chen Yifeng)

/