Structuring with Mindscape and Landscape

/

Translation | Wanli Mo

Proofreading | Patrick Kunkel

I will show you the terrace. It is surrounded by trees and gives me the illusion of living in the country.

The terrace is wet from recent rain. The overcast sky accentuates the purple-grey of the stone. The surrounding rooftops are covered with dense vegetation.

They cut down the thickest part; it was also the tallest, and from inside I could see it outlined against the sky. Those trees had become familiar images. They recalled the loneliness and depth of nature that is indefinable, almost musical. Although it is only a matter of a few terrace trees, I don't think forests, seas, and authentic countryside could give me such an acute emotion.

We go back inside the studio. It is getting dark out and the winter sky moves slowly across the glass. The architecture turns on the table lamps, which cast a violent white light. The rest of the room remains in shadow.

It was also a rainy day when I first read this paragraph by Luigi Moretti; I was sitting at a corner of my office as daylight was gradually ebbing away, the tops of phoenix trees waving in the skylight. When I read this passage, I felt a deep sense of connection to Moretti's words written in 1936. I read two of his other essays, Structure as Form, and Ideal Structures in the Baroque and in the Architecture of Michelangelo, just the day before. And despite the tremendous epochal and geographical gap, there was something echoing in his thoughts on structure that resonated with mine. Although I could not visit the architecture he wrote about, I noticed that from ancient Rome to Renaissance, from the prewar Italy to my thoughts by the windows of Deshaus' new office, a textual reading of architecture offered an understanding of structure whose technological substance evolved into a cultural symbol to became a constant subject that transcends classical and modern periods. While sometimes it seems that the word structure becomes too abstract as it shifts between multiple meanings, Moretti's words create a rich understanding of architecture.

For a very long time, we sought to understand traditional architecture such as dwellings and gardens in Jiangnan area from a perspective that emphasizes exterior space. For Atelier Deshaus, an important spatial feature of traditional Chinese architecture is that it usually treats exterior and interior space as equal, if not prioritizing the former over the latter. Such an attitude perhaps comes from the notion that exterior space might be more easily translated by modern designs due to its narrative relations. As for interior space, since wood and stone structures are no longer protagonists of modern architecture, it is abstracted into a series of void boxes as spatial relationships become a priority in modern designs. Influenced by new structure system and modern art, from Mondrian to de Stijl, from Loos's Raumplan to Mies's flowing space, the concept of space is always abstract. Following this line of thought, Le Corbusier's Dom-ino system seems to provide more possibilities by emphasizing the spatial freedom offered by omitting load bearing walls. As a result, columns seem to be the only structural system, drawing an analogy between the interior space of traditional architecture and that of modern architecture and connects the primitive intention of being supported to our bodily perception. Yet, if one carefully examines Corbusier's work between 1914 and 1921, it could be observed that he went to great lengths to hide columns in his buildings, as he made a point of hiding load-bearing elements in cabinets and partition walls. Looking back at some of our projects such as the Jiading New Town kindergarten, we also attempted to fully eliminate the spatial impact of columns. In some cases, walls were designed as thick as columns (600mm thick) to conceal their spatial impact. After 1925, structural columns began to appear in Corbusier's architecture, but it seems that he didn't consider much about their spatial impact or cultural meaning, at least when compared to the work of August Perret. In most of Perret's projects, columns represent the persistence of classical culture, adding cultural meaning through the meticulous chiseling of concrete. Perhaps Kazuo Shinohara was one of the few architects to engage with a sense of thingness by reducing the cultural meaning of the structure in his space making. This concept is most present in his White House, in which he creates a uniquely Japanese space with a wood column framework; the isolation of the column in the White House could be influenced by this cultural tradition. While Shinohara added well-focused articulations on this cultural basis, Corbusier's buildings clearly seem to belong to a different tradition, one that comes from the Italian Renaissance.

It was not until the summer of 2014 when I was visiting the middle temple of Tianwang Temple in Changzi County, Shanxi province, that the interior space of traditional Chinese architecture caught my interest again. As the building was under maintenance, the Buddha sculpture was removed, leaving gigantic wood beams that intensified the experience of the space. The structure's impact on the space immediately reminded me of the Long Museum West Bund that was about to be completed. It seems that the reason why the interior space of traditional Chinese architecture no longer influences our modern architecture is that the wood structure system based on Yingzaofashi (Treatise on Construction Methods) is no longer feasible with today's construction methods. While traditional interior space is built by well-defined methods of construction, today's structures are too easily overridden by a thin layer of white paint, as either an outcome of spatial abstractness or just a lack of consideration. A way of returning to tradition is to return to the role of structure in space making; by doing so, structure can become an element that connects places, programs, bodies and even time. In Atelier Deshaus's projects after 2014, structural consideration clearly gains more significance.

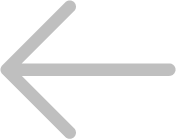

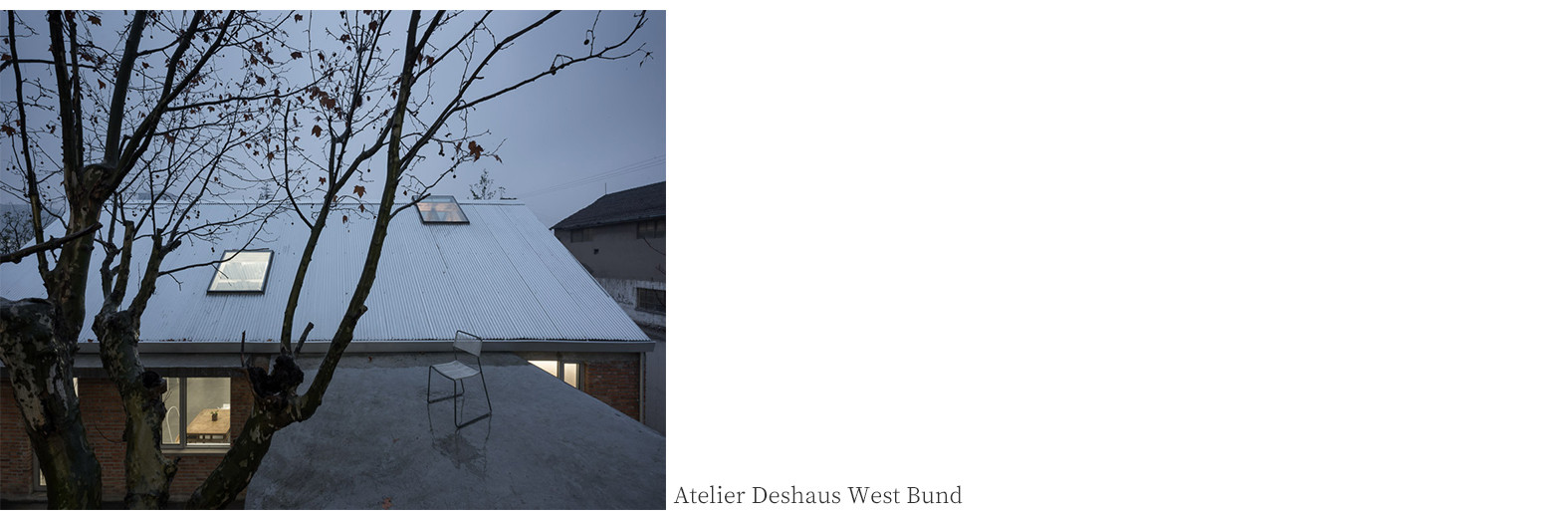

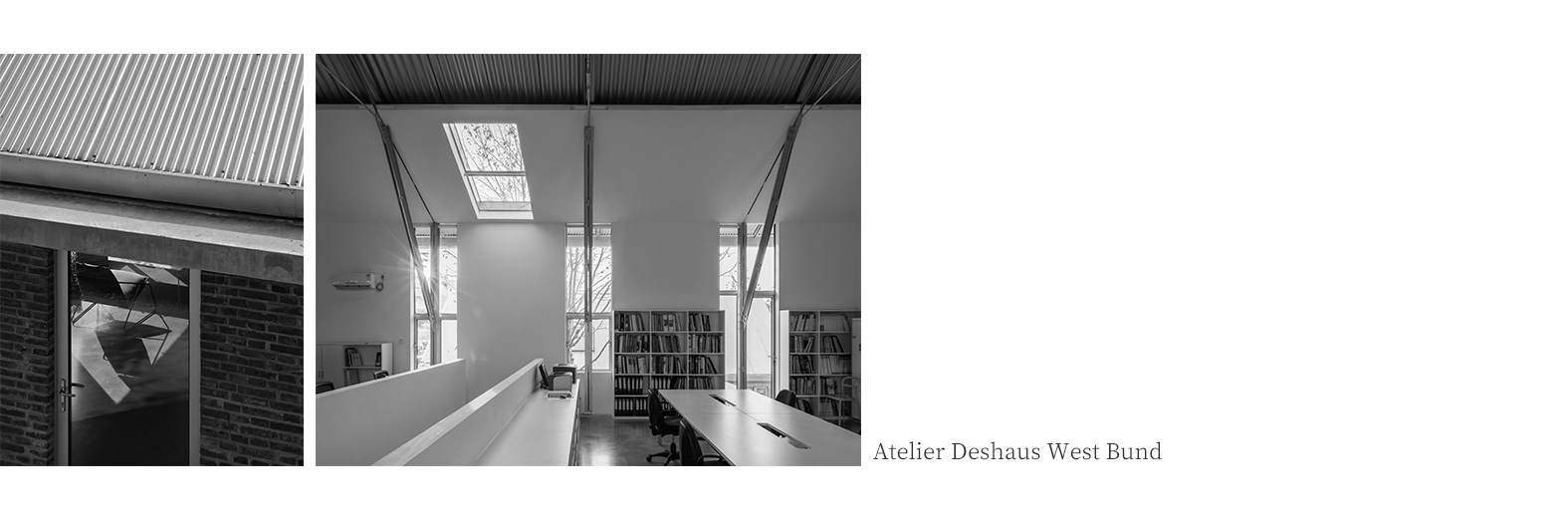

With a newfound awareness of the many implications of structure, in 2015, we designed and built our new office in the West Bund area. A temporary building with a five-year use right, the new office is located in an existing parking lot that previously was a part of the Shanghai Aircraft Manufacturing Factory campus. The parking lot was an auxiliary facility that served the nearby aircraft warehouse, which is now the West Bund Arts Center. There is a200mm thick concrete substrate layer and several trees on the site; some of the trees were newly planted for shading, and some were left over from the site's original use. The new office occupies the space left by these trees. Three big trees from the original campus period, a cedar and two phoenix trees, are either enclosed in the courtyard or leaning toward the new buildings. As we positioned our building on the site, we began to form an intuition about how we wanted to build our office. We chose to use the existing concrete substrate layer to avoid paying for a new base. We also incorporated three old trees into our design to establish a physical connection with the natural landscape and a temporal connection with the previous aircraft manufacture factory.

Programmatically speaking, our office consists two types of space: a working space with heavy everyday use of computers and an auxiliary area that includes a meeting room, a modeling room, a storage space, an accountant's office, mechanical space, a kitchen, a restroom, and several other service spaces. These two types of programmatic space correspond to two spatial forms: a large open space and smaller enclosed space. The small space is enclosed by brick masonry structure, which allowed us to build directly above the existing concrete substrate and also requires a lower height, which is suitable for auxiliary space. Open working space with a light steel structure system is placed on the second floor to provide enough lighting. Placing most activities on the second level also allowed us to address Shanghai's humid weather and high underground water level. While the size of each auxiliary space and the required adjacencies determined the wall layout on the first floor, the scale of office furniture sets column locations and bay size on the second floor. In order to keep the original office layout in our previous office, we proposed a 3.2-meter bay, which not only allows for the use of old furniture, but also indicates a temporal continuation of the old space and its scale.

The next step was to refine our scheme, further articulating its nuances. We observed that the relationship of each element and its specific function to the environment was a back and forth process in which many design decisions were interrelated, and one move could be the result of several considerations, or without any specific causes, or just the consequence of the subconsciousness. We first determined the second floor plan based on the above-mentioned consideration. As the desk layout of the second floor became clear, positioning of the windows became clear. Then we made decisions on column locations and roof structure. If the columns were located along the window walls, they could cause confusion with the enclosing walls, and if we used a triangle roof framework, the space could resemble too much that of a factory or a warehouse. To resolve this matrix of design considerations, we used a structural system with vertical columns, diagonal bracings, and pulling rods. Diagonal bracings not only divided the whole space, but also created new spatial meanings, and columns were positioned at the mid-point of each window to emphasize the framework in this particular space. This produced a visually distinct and autonomous impression of structural support. The space ends at the mid-point between columns, which we designed as a gable wall despite its steel column and beam structure. After we determined the positions of windows and steel columns on the second floor, we were able to determine the position of openings in the first floor masonry wall. Based on structural rationality, windows of upper floor and lower floor stagger. After we carefully position the staircase and the entrance, the design of this two-story building on the east side of the site was almost finished. As major spatial dimensions were set, the task became to match the dimensions of ready-made industrial material sheets to that of our design. A both economically reasonable and aesthetically valuable method could always be sought. Here, aesthetic value refers to two aspects, the weighing of the proportion of space and its openings, and the treatment of material joints.

As we moved forward with the design of the two-story building, another design consideration we had to address was how to make the other volume, housing a conference room and two partners' offices, enclose trees and courtyard. After careful consideration, we decided to use a distinct one-story mass with a pitched roof that created a balance with the two-story pitched-roof building. As roof span differs, different sloping gradient and eave details produce a tension between their parallel positioning. A connecting corridor, housing a kitchenette and restrooms, extends to their eaves and permeates into their interior space, uniting them both formally and spatially. The roof was designed as a dynamic folding surface to leave room for existing phoenix tree branches. Establishing a clear mathematical relationship with the structure and the interior space, the position of skylights developed in relation to the tree branches, creating a mutual dependency between architecture and plants that calls to mind the following passage:

As the rain had just stopped, the terrace floor was damp. Water was still trickling down from the rain pipe at the folding corner, into the bent metal pipe that was I had picked up from a construction site a while ago, and finally was drawn to the tree roots. The dark branches of the phoenix tree of winter were reflected in the damp terrace floor. The silver waved metal roof panel almost melted into the bright white sky. A warm yellow light shimmered behind the skylight and the sky gradually dimmed.

This scene made me feel like I was also living in the countryside just like Moretti. Such was my impression when I first visited the West Bund. The area was still in a preliminary phase of urban redevelopment, and was deeply connected to the Huangpu River, perhaps the most intact and powerful natural existence in a bustling metropolis like Shanghai. Thus, it implied an opportunity of a peaceful co-existence of architecture, the city and the nature.

My response might appear entirely unrelated to structure, but the impression I felt had a significant impact on my creative process as I was designing the building, and lasts even after the building is completed. Perhaps the architect, the only one who can imagine reversely a process in which a vacant site is gradually occupied by bricks, tiles, and structural frames, a process in which space emerges from nothingness and who is more deeply affected by this impression than anyone else involved in the construction process. Eventually, what emerges from this inspiration is an outcome whose coming into being is a full of an architect's expertise and value and is far more worthy of discussion than the outcome itself. We often feel that as a project is finished, certain strength during the construction process is also lost. Perhaps, it's because that at that final moment, structure retreats in that final space.

The decision to use a mixed structure system made of light steel and brick masonry was more than a consideration of reducing the cost of a temporary building; such a choice was also influenced by the temperament of the site. Once filled with docks, warehouses and airports, its industrial characteristics are still present and will remain as an indelible mark of the site's heritage. The pitched roof, a typical image of home, is then no longer simply about rain proofing due to the site's history. At the moment when architecture takes form in consideration of also structural form, its association with the existing site predetermines that it will transcends technical contents toward cultural meanings. It is through this process that the meanings of structure could be studied with multiple possibilities.

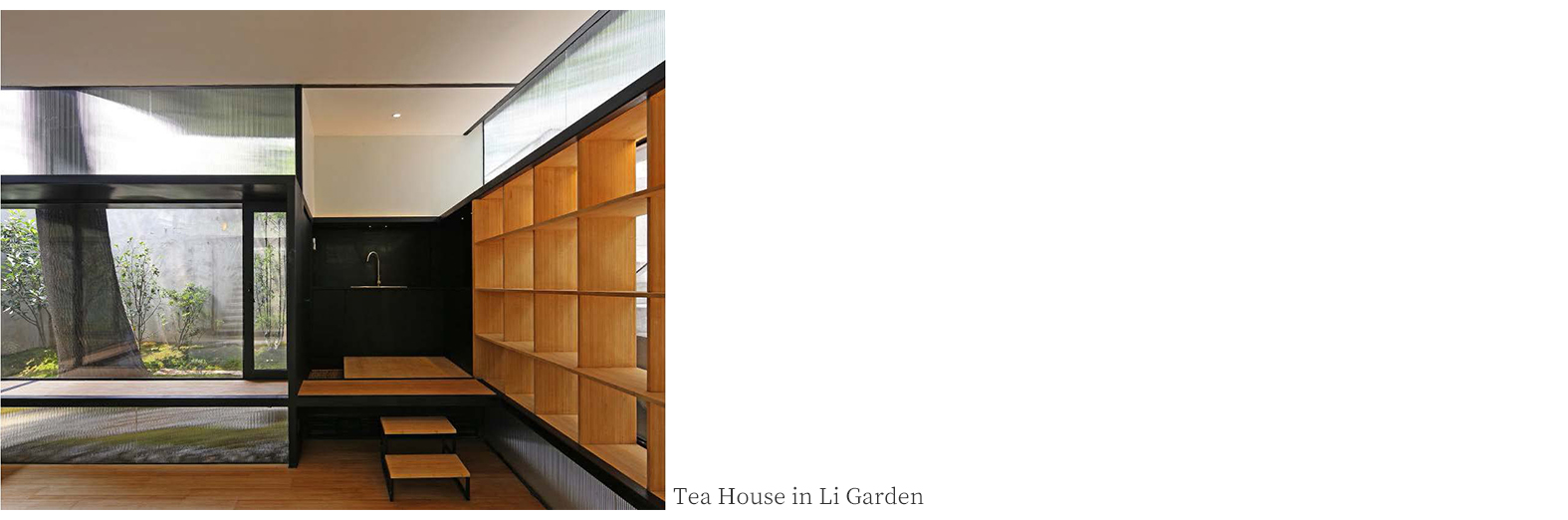

Our design for the Exception Clothing is about 40 meters away from our office. This design places a teahouse in a small courtyard around 100 square meters where a tall paotong tree grows. The courtyard, enclosed by walls on its north and west side, has a small corridor and a stair to the adjacent office building on the east and south. Due to the small size of the courtyard, our priority was to create a teahouse that would occupy as little space as possible.

We began our analysis with an investigation of the site. After a thorough examination, we decided to locate the teahouse as close to the paotong tree as possible. Taking advantage of the nearby rear wall, the tiny space between the wall and the teahouse becomes part of the teahouse's interior space. This activated the tree whose diameter is around 90 centimeters, transforming it into a crucial spatial component for the teahouse. We also attempted to reduce the teahouse's actual footprint without making it perceptually too narrow. Our proposal created a concrete base above the ground to define the teahouse's realm while allowing us to shrink the building footprint as much as possible to extend the courtyard space. We also noticed that while the base of the teahouse could be small we could extend the upper part of the building beyond the footprint to emphasize the scale of certain behaviors such as standing, sitting, seeing, focusing, and contemplating, to generate an awareness of the position of the human body.

The spatial relationship between the human body, the teahouse, and the courtyard are expressed through three layers of cantilevers. The first layer occurs at the height of 45 centimeters from ground. A horizontal plane for sitting that defines the boundary between the interior and the exterior, it implies a human body that is sitting toward the interior space. In order to create a more active relationship between the teahouse and the courtyard, this plane is located on the south side of the building and faces the courtyard, giving the space above it back to the courtyard. The second cantilever is located about 1.8 meters from the ground and enlarges the perceptional scale of the interior space, making it resembling that of a standing person opening his arms. This cantilever would not influence the activities under the teahouse eaves, although people taller than 1.8 meters would naturally bend slightly to adapt to this space without discomfort. The third cantilever layer is the covering roof, which defines multiple spaces under its eaves. While the teahouse only occupies 19 square meters, the roof covers an area of 40 square meters, highlighting the spatial relationship between the teahouse and the courtyard in different directions. As the roof bends down toward the main courtyard, it establishes the teahouse's directionality and frontality.

We chose to use slender structural beams with a 60mm by 60mm square section for both horizontal and vertical structural components. These dimensions not only suit the scale of the teahouse, but also reduce the structural impact on the space. As all horizontal supporting components are of the same dimension, their abstract linear forms function as more than load bearing elements; their design allows them to play a formal, spatial role in the building. The dimensions of these structural elements also respond to the dimensions of furniture, creating a more intimate relationship with human bodies. An 8mm thick thin steel plate constitutes the roof, and a layer of insulation sits above it, anchored by steel reversed-ribs that keep the roof flat. These reversed-ribs not only eliminate the sense of modesty and temporality produced by the fact that the roof is covered with black waterproof membrane, but also generate a sense of lightness and precision for the teahouse by creating an extra-thin roof edge.

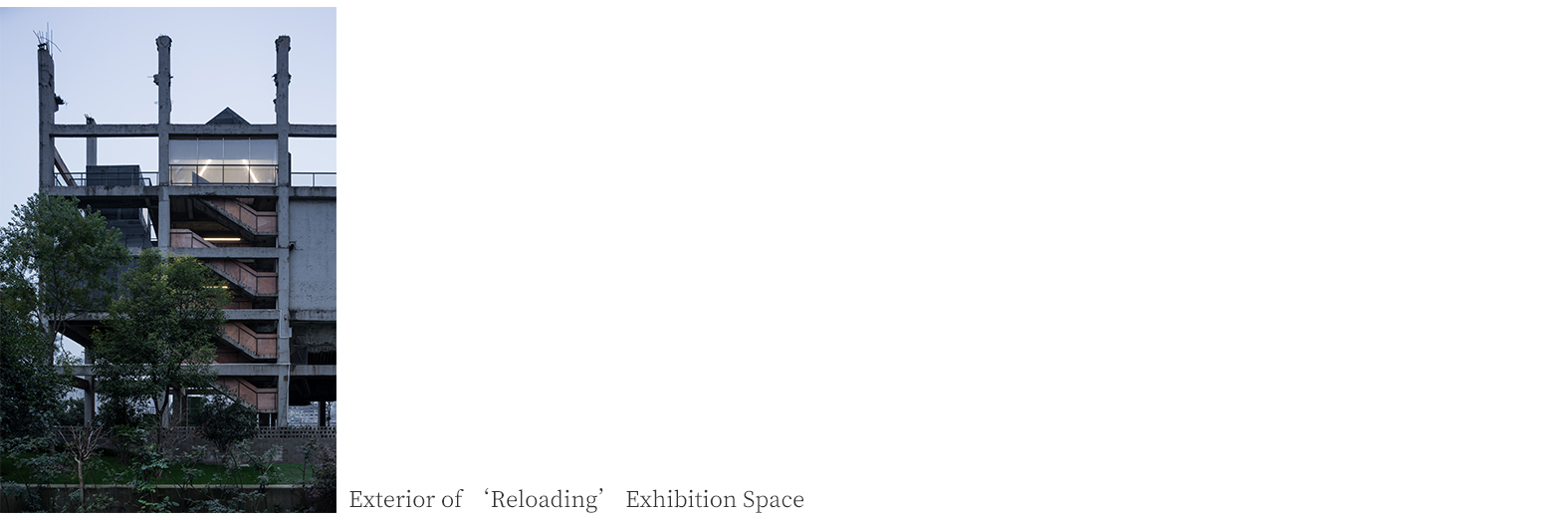

The old Baidu Port coal bunker, a renovation project located along the East Bund of the Huangpu River, is an existing industrial building with a history that dates back to the Guangxu period in the Qing dynasty. 1995, the annual handling volume of the Old Baidu Port reached 9,350,000 tons, and with the development of Shanghai in the past two decades, these ports were repurposed as parks along the river. When we worked on the project, the question of how to best reuse the existing structures had become an important local topic. The coal loading dock had been abandoned for years, and was going to be a temporary site for the exhibition Reloading, an event of the 2015 Shanghai Urban Space Arts Season, which exhibits exemplary cases of Shanghai industrial building renovation projects, and our task was to transform this industrial wasteland into an exhibition site within about a month's time.

The coal loading port had been renovated two years ago, and although a new building was proposed and most of the existing structure had been removed, the project stopped when its roof and infill walls had been taken off, leaving only a concrete skeleton. This called to mind Peter Eisenman's quotation of Derrida in his introduction for The Architecture of the City:

"...the relief and design of structures appears more clearly when content, which is the living energy of meaning, is neutralized, somewhat like the architecture of an uninhabited or deserted city, reduced to its skeleton by some catastrophe of nature or art. A city no longer inhabited, not simply left behind, but haunted by meaning and culture, this state of being haunted, which keeps the city from returning to nature..."

The coal bunker is just a skeleton. I visited this ruin for several times and each time, it felt like entering into a kind of nature. Without enclosure, paint on the structural skeleton quickly went off, revealing the underlying concrete.

When Derrida discusses how the state of being haunted "keeps the city from returning to nature", he refers to that ruined cities and architecture are in the process of returning to nature. In his essay Structure as Form, Moretti writes, "... to the density and the tension particular to every point of the architecture space. These points would have a very different density and tension were they in a solely structural, formal, or functional space." Moretti seems to describe a condition in which function and form both give way to structure, a condition that is very evident in the coal bunker. As its function for shipping was lost, the structure that was built for such function begins to express an unnamable tension at present time.

Standing on its top floor, I was surrounded by a broken colonnade lined by exposed reinforcement bars at the top. The wide Huangpu River turns nearby, running past the building, carrying boats past the structure. At that moment, I noted that this deserted coal bunker resembled a natural park, whose meaning could be again completed with just two small new structures. With a pitched roof, one of them is placed at the end of the colonnade platform, rendering its spatial atmosphere immediately solemn. It is like a small church, flanked by two colonnades that create a sense of enclosure as well as an extraordinary monumentality that evokes classical antiquity. We saw this intervention as an experiment, where the structure becomes neutralized, its original functions are lost, and new meanings are produced as new functions and volumes are placed.

A fixed exhibition circulation was designed based on existing conditions. Visitors first enter the colonnade platform located on the fifth floor from a gigantic steel stair that transforms from an existing coal conveyor belt. The platform is the first of several dramatic spatial moments, providing an extraordinary river view. A slender steel canopy draws people into the exhibition lobby. Here, two rows of black metal pipes function as both detectophones for sound installation inside the coal bunker funnels as well as spatial components that enhance the room's directionality. Walking down from the lobby, visitor would pass the open video room on the fourth floor and arrive at the themed exhibition hall and the temporary lecture hall at the third floor. Capitalizing on the existing openings on the ceiling, the themed exhibition hall's skylights cut through the fourth floor plate and could be seen at the top floor. As a hint of newly added exhibition volume, they emphasized the downward circulation. The main exhibition hall is located on the second floor, which is also the narrowest and lowest space. An exhibition of architectural models is arranged in the space between coal funnels. Their slanted coarse concrete surfaces are used for video projection, indicating an overlapping of time. In total, there are eight exhibited cases, eight architectural models, eight videos, and eight soundtracks created by a sound artist that transform the space into a musical hall. The music is quite unforgettable and from that moment, for me, sound also becomes a way of evaluating space architecturally.

From the exhibition hall located on the second floor down to the ground floor level, what awaits visitors is a sunken grand hall covered by eight coal funnels. When visitors pass different funnels, they hear the sound of underwater motor, the sound of a metro passing, the sound of coal dropping, among other noises recorded by the sound artist. This allows the funnels to become containers of sounds, making the exhibition an integral whole for visitors.

The renovated exhibition space uses almost every element remaining from the building's previous use. Only two small black new structures are added: simple as multi-layer boards and plasterboards that wrap their light steel framework around the outside and inside. The round skylight of the lobby carefully avoids this inner structural framework, but casually reveals certain added elements. We also intentionally left a steel column in the main entrance, implying the larger structure and making people's encounters with the structure more natural. The black box is covered with naked modified tar waterproof sheets, which has a soft reflection similar to the shining texture of a horse's mane. While this material is rarely used on the outside, it all of a sudden it takes on a dignified hue within the setting of ruins. With the placement of two small black boxes and exhibition activities, the deserted coal bunker, once a ruined structure evolving toward nature, become once again an architectural structure.

A work of architecture is consumed according to the visible expression of its surfaces, its skin, independent of how these forms are internally connected to structure of concrete reality, weight and materials, and tensions. The degree of correspondence or interdependence between the structure to be consumed, the visible structure, or simply architecture, and the real structure can vary from exact identification, to slight alternation, to complete divergence with the real structure. Of the two extremes, absolute divergence belongs to the realm of scenography. One need only think of the commemorative mechanisms of the Baroque. The other extreme is in the field of engineering, deaf and devoid of spirituality and therefore outside the world of architecture. Or instead, the absolute divergence can touch the very pinnacles of this art.

The paragraph above, from Moretti's 1963 article, discusses the architecture and structure of Michelangelo and the Baroque period, and echoes what David Leatherbarrow and Moshen Mostafavi describe as surface architecture. It also refers to Kazunari Sakamoto's concept of structural thingness. Thus, the above paragraph is in a sense contemporary. In the introduction of Surface Architecture published in 2002, two authors writes:

"Once the skin of the building became independent of its structure, it could just as well hang like a curtain or clothing. The relationship between structure and skin has preoccupied much architectural production since this period and remains contested today. The site of this contest is the architectural surface. "

In a different article published in 1978, Sakamoto also writes that "if we accept that architecture could be regarded as symbol or as an arrangement of symbol, then, the structure in a material sense becomes a way to achieve this. That is to say, there's a separation of structure as what represents and structure as what is represented, despite that in reality, the two aspects are intermingled and could not be entirely separated." While Moretti and Sakamoto's views have certain similarities, Leatherbarrow and Mostafavi view the surface as a phenomenon that is independent yet connected with the discussion of structure. The Dingyi Building of the Artron Shanghai Arts Center represents Deshaus's thinking on this topic. The project is also one of the eight exhibited cases at the Reloading exhibition at the old Baidu Port coal bunker. In our newly built temporary pavilion, the Pavilion of Flower and Grass, the relational question of architectural surface and structure is brought up again.

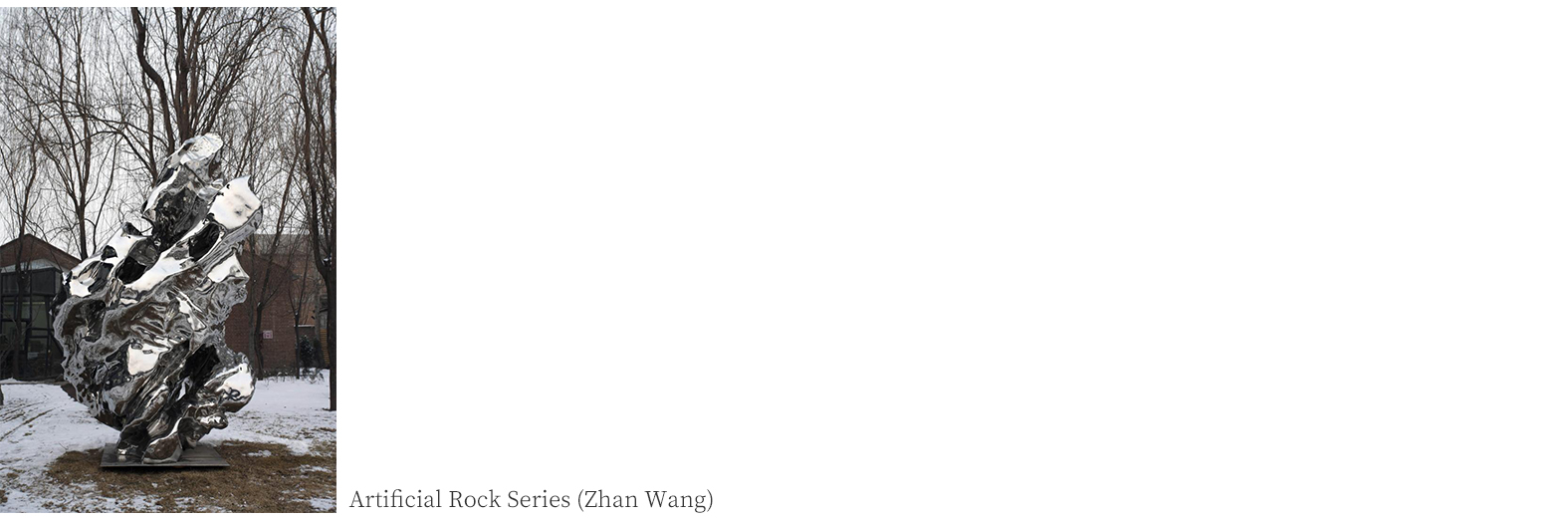

Atelier Deshaus' Blossom Pavilion, created with the artist Zhan Wang for the Shanghai Urban Space Arts Season 1+1 (Artist +Architect) Spatial Arts projects, addresses the question of surface and structure. An important part of Zhan Wang's work are his rockery sculptures made of stainless steel. When I visited his studio, I was captivated by his recent steel rubbing pieces. In these pieces, the artist places an extremely thin layer of flat stainless steel onto the ground or any other material and rubs its texture onto the stainless steel with a softly packed hammer, causing an industrial material to bear natural information and the trace of handcraft while simultaneously displaying its own materiality. This method is similar to how the Swiss architects Herzog and De Meuron treat materials, which are also strongly influenced by artists like Rémy Zaugg and Joseph Beuys.

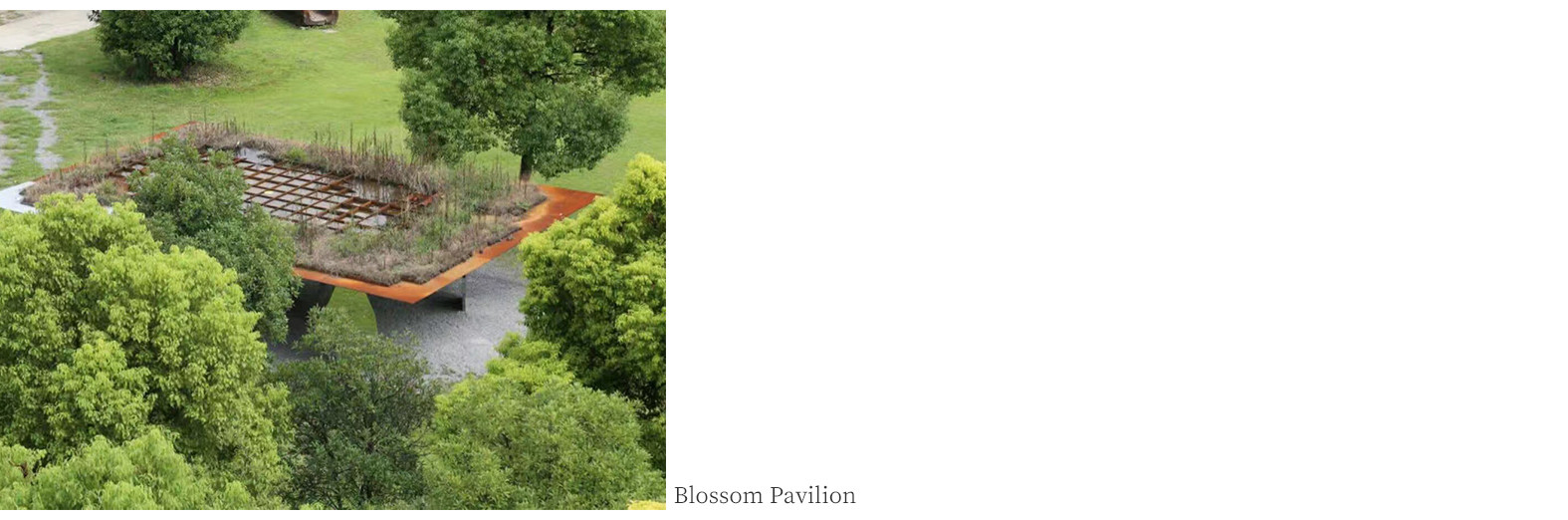

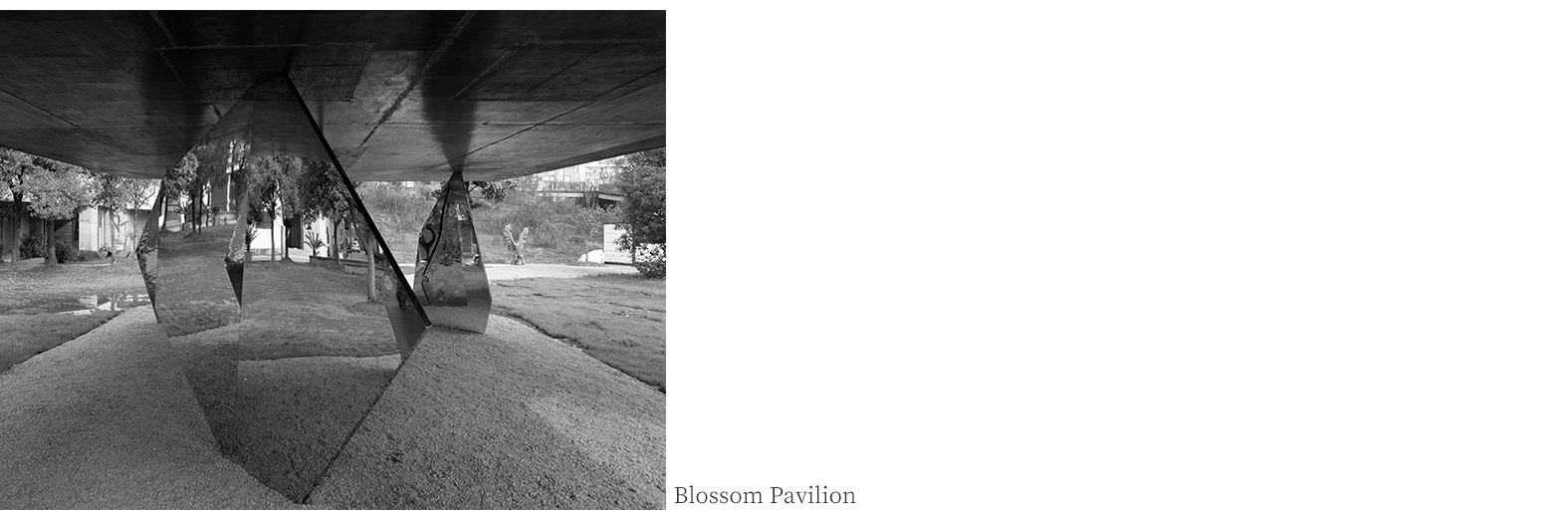

The Pavilion of Flowers and Grass is intended to be a shelter space housing a cafe and a rest stop in the central lawn of Red Fang. It is an opportunity for the architect to express concepts that resonate with the creative work of the artist.

Supporting and covering are two of human beings' most primitive modes of spatial construction in order to shelter themselves from sun and rain, and during the evolution of construction history, as the principle of reason and science gained more favor, engineering gradually became the technical core of shelter. Our pavilion adapts these principles through the meticulous calculation and scaling of each element; in this pavilion, the 12 meters by 8 meters roof is a steel plane supported by 8mm and 14mm beams placed in an 800 millimeter by 800-millimeter grid based on load distribution. Rib panels in a cloud shape with a thickness of 14mm thick and a height raging from 50mm to 200mm based on load bearing condition are placed on top of the roof plane. The spaces between ribs are used as beds for roof planting. The roof takes on the shape of a natural topography and is supported by 6 steel supports with either a 60mm by 60mm square section or an A shape section, according to the spatial layout, allowing us to produce a Miesian minimalistic structure is completed fundamentally rooted in the principles of engineering and generating shelter..

Despite our desire to address the spatial limitations of structure, we did not place the location of each support in accordance with the most reasonable structural principle, nor did we force each element to display its original material appearance. While we could have limited our design to the most efficient solution for a pavilion, we chose to base our design on our initial inspiration of a space supported and defined by a Rockery cut into slices. In the same manner that Zhan Wang treats the stainless steel sheet, supports placed according to principles derived from engineering and efficiency are wrapped in stainless steel rubbings in mountainous rock shapes, creating a spatial sense of a rockery. Through this process the architect deconstructs and transforms the artist's rockery sculpture into an abstract rockery-like space. Wang chose to apply stainless steel with a texture of mountain rock to one side of the slice supports to reflect the surrounding natural landscape with a blurring effect.

With an inspiration from an artistic work, the architect is able to enter the rhetoric of a primitive space in a similar contemporary way. In the project, what actually supports roof is the inner steel columns inside the stainless steel slices. As a cladding of the structure, stainless steel surface is both a cultural symbol created by the artist Zhan Wang and a representation of the structural load bearing condition. Meanwhile, it creates a kind of space that is enclosed both physically by solid entities and immaterially by reflections and becomes a rhetorical means of communication between architects, artists and the public. After the position and shape of each support was determined, the eventual spatial and structural form underwent multiple rounds of mutual adjustment. The rationality of this back-and-forth process is expressed in the cloud-shape rib configuration above the steel roof, which is visually absent inside the pavilion. This process produces a spatial tension that is achieved through a structural illusion that counter to what might be expected. As structure serves spatial intention, it retreats behind space and meaning, expressing its being through support location and roof topography.

The inner structure and outer landscape both construct the meaning of architecture. However, we seem to be more accustomed to the idea that the inner expression of structure has to be forsaken because it is shaded by architectural surface. Yet for me, two are of equal significance; when we just finished the structural framework of our new office this summer, I wrote in my diary, "Thinking about the air. It connects substances that are known or unknown, materialized or inmaterialized. And suddenly it was wrapped within an enclosure, becoming something dark or luminous, something tense or at ease, yet something always silent. At that moment, the architecture is also a ruin, far away from the world, undisturbed and isolated. And such moment is transient as I know that that architecture immediately becomes worldly". When I wrote these sentences, I was thinking of the moment when scaffolds were removed at the Long Museum. At that moment, it become evident that although the structure eventually retreats behind landscape and worldliness, it is also the very confirmation of architecture's come-into-being with its value persisting in the tide of time.

(Liu Yichun, edited 2016.10, first published 2016.4)

/