Between "Situatedness" and "Objecthood"

Qing Feng

/

Translation | Xie Yunling

Proofreading | Qing Feng

"On the Immediacy of Objecthood and Situatedness of Architecture" is the title of a solo exhibition of Atelier Deshaus at Studio-X in Beijing. "Immediacy" means getting close; situatedness refers to architectural space and the milieu or atmosphere along with it, while objecthood refers to the materiality of architecture. [1] It is evident from the title that architects in Deshaus defined their architectural practice as an exploration of two major ontological elements of architecture, situatedness and objecthood. It is like a constant process of approaching the essence, with twists and turns due to perplexing goals and paths, which is also implied in the Chinese version of the title, “即境即物,即物即境”, as the switch of character order points to a balance and choice between those two components. If it is not mistaken to say that Deshaus were inclined to create situatedness in their early design works, then there is a clear tendency of giving higher priority to the construction of objecthood in their current works. Sharp contrast between Long Museum and their former works reflects this transformation. Behind the design strategy and architectural vocabularies are architects' changing reflections on the essential values of architecture and the way to realize them.

Many people still believe in the classical modernistic idea that a new era will form new architectures, and with this as a criterion, arguing that modernism has gone out of time or been dead. Yet in most cases they neglect the potential impact of modernism as an ongoing tradition. For contemporary architects, modernism is no longer a choice with consciousness, but cryptic subconsiousness, a premise that has already been accepted without awareness. No longer manifest in ordinary discourse or conspicuous in practice, modernism, as a matter of fact, has infiltrated into architects' fundamental ideas of the origin and destination of architectures. When we accept some kernel factors of this tradition unconditionally and take it as the starting point of architecture, we discard our opportunities to shake off this tradition and receive other possibilities instead. For those who cherish these opportunities, they not only need to change practical approaches, but also to challenge the idea they once adhered to. This task is far more demanding because it takes courage to be self-critical and self-conscious to construct and apply theories, and requires sensitivity to accept other traditions.

The early works of Deshaus can be described as an outcome of such introspection and reselection. A new type of element, excluded from the tradition of modernism, was introduced, and that is the spatial context of Chinese gardens and towns in Jiangnan area. It is not uncommon for many contemporary architects to enrich the monotonous universal language of modernism with regional culture. And for the architects of Deshaus, who lived and worked in Jiangnan for most time of their lives, the primary strategy of such enrichment is a translation of local spatial typology. This translation not only helped Deshaus to jump out of the constraints of Cartesian coordinate grid in their works during that period, but also empowered them to absorb various spatial modes with more freedom.

"It goes without saying that our practices have been deeply entrenched by our understandings of the geo-cultural Jiangnan, consciously or subconsciously. Most of our previous built projects highly resemble a self-sustaining cosmos...which derives from literati gardens"[1] So described Deshaus the key role the spatial prototype of Jiangnan gardens plays. From this prototype they abstracted three concept to facilitate the spatial translation, which are detachment, border and juxtaposition. Among the three concepts, detachment and juxtaposition are more closely related. Together, they constitute an order of space organization with Jiangnan character. "Detachment" implies preventing the specificity and independence of partial units from being assimilated or absorbed by the general order. To some extent it even requires a confrontation against the unified whole to preserve an alienated relationship. "Juxtaposition" depicts the relationship of multiple elements that are in a detached state. It also suggests not regulating partial independent units with a single rule by force, preserving their differences rather than covering up the occasionality and complexity caused by conflicts. This organization logic is what Deshaus thinks gardens in Jiangnan area keep to, which is different from the universal order that modernism aspired to. The third notion, "border", contains multiple layers of meanings. A border is the fundamental condition to construct the independence of units, and on the other hand, it circumscribes a protected area in social life where people can create a "small world" that belongs to themselves and is separated from the exterior one. In Chinese culture, retreating into one's own small world and complete the self-cultivation is a continuous tradition for Confucian intellectuals. Such attitude is typically exemplified by the enclosure created by the high walls surrounding the private gardens of literatus in Jiangnan. "The Chinese concept of 'the unity between heaven and man' takes place in a walled courtyard and the walls serve as a 'border'." [2]

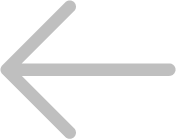

The three concepts well explicate the characteristics of the major works of Deshaus during 2003 to 2010, such as Youth Center of Qingpu, Office Building of Qingpu Private-owned Enterprise Association, Jishan Software Park in Nanjing, etc. Deshaus uses the notion of "situatedness" to summarize the common attributes of works in this period. By way of pursuing the immediacy of situatedness, they succeeded in introducing the specific spatial relationship in Jiangnan region to the mature architectural vocabularies, passing over the constraint of the traditional models of modernism. From the individual perspective, introducing traditional context, separating from the monotonous geometric order of modernism, and bringing occasionality and complexity back again, can be seen as Deshaus's response to the geo-cultural tradition. But from a grand historic perspective, it is a subversion against the long-standing Descartes creed in modernism, which enabled Deshaus to expand its own architectural vocabularies and shape a specific identity in their works.

Even so, Deshaus's works are still under the heavy influence of modernism, especially in some core concepts. This can be seen in the close relationship between the notion of situatedness and the space paradigm of modernism. The concept of space is prevalent in architectural discourse now and one crucial reason for this is that in architects' opinion, we have found "the purist non-reductive substance of architecture--a feature which is so architecturally unique that can distinguish architecture from other artistic practice." [3] That is to say, the concept of space, signifying the distinction of architecture, lays a solid foundation on which architecture can be distinguished from other arts and attains its autonomy. Moreover, the close relevance between the concept of space and modern science and modern philosophy entitles architectural theories to gain some academic advantage from the theoretical system that people believe is "deeper", adding scientific and philosophic aura to architectural studies.

However, by embracing the dominance of space, architects have to accept the limit and restrictions implicit in such categorization, thus restrain their own architectural vocabularies. Such sacrifice has been exposed in many modernism buildings, and now it also appears in Deshaus's works that relied deeply on the notion of situatedness. By putting special emphasis on space and its atmosphere, they nevertheless have to pay the price of suppressing materiality and meanings to attain the purely abstract geometric vocabularies of architectural space.

The core of situatedness is embedded in the concept of space, suggesting that the space paradigm still controls architects' thinking in the decision process. The assumptions and tendencies concealed in it directly leads to the strong abstract geometrical relationship in their woks. Perhaps the architects have extricated themselves from Descartes' prejudice against irregular juxtaposition, yet they still have great lengths to go to overcome the worship for mathematical and geometrical purity and the repression of bodily and sensory perception. After all, these ideas have been rooted deeply in the architects' understanding of architecture through the arcane concept of space and only a more determined decision can resist its temptation. This is why architects in Deshaus put "objecthood" into consideration. It relieves their recent works from the restriction of the space paradigm, making a huge difference between Long Museum and former works. For those who have self-consciousness of theoretical construction, an alternation in a concept will change the whole system from the bottom to the top indeed.

How come objecthood is of pivotal impact? To some extent, it is regarded as the opposition of space, for what the space paradigm suppresses are precisely the fundamental attributes of an object, such as hardness, weight, color, tactility etc, what people bodily experience in ordinary life. But it is precisely in the everyday engagement with these properties, human activities come to have meaning. Furthermore, a specific thing is usually a carrier of meanings as well, recalling certain cultural memories with its form, texture, construction, etc.

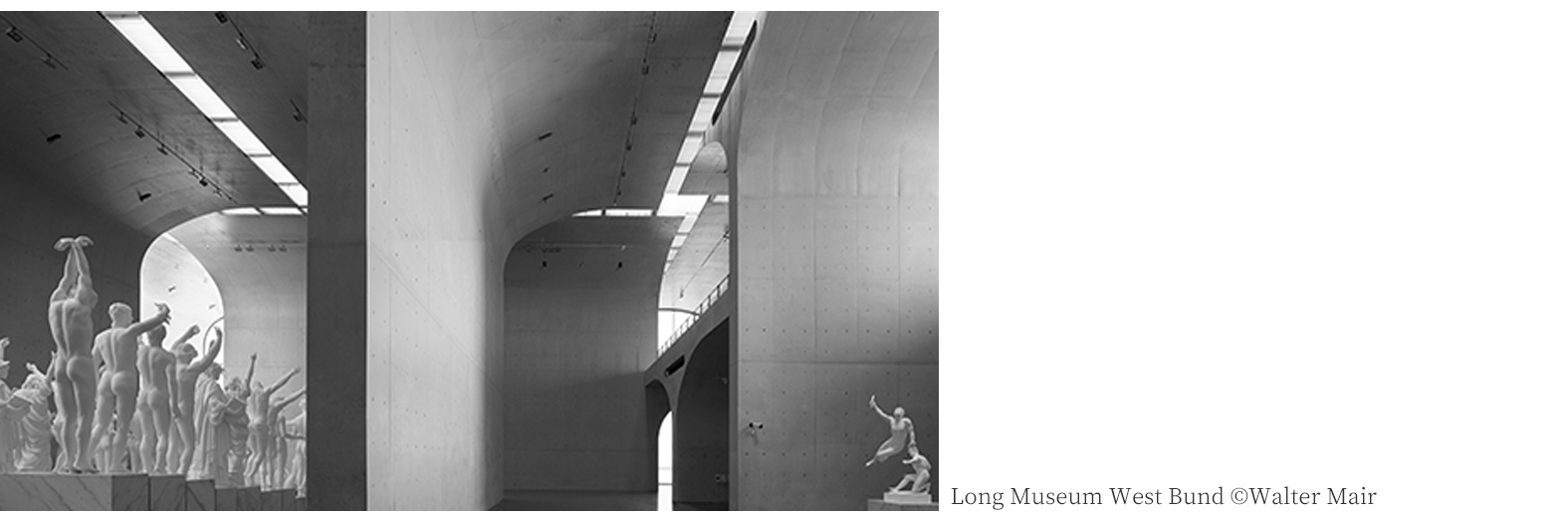

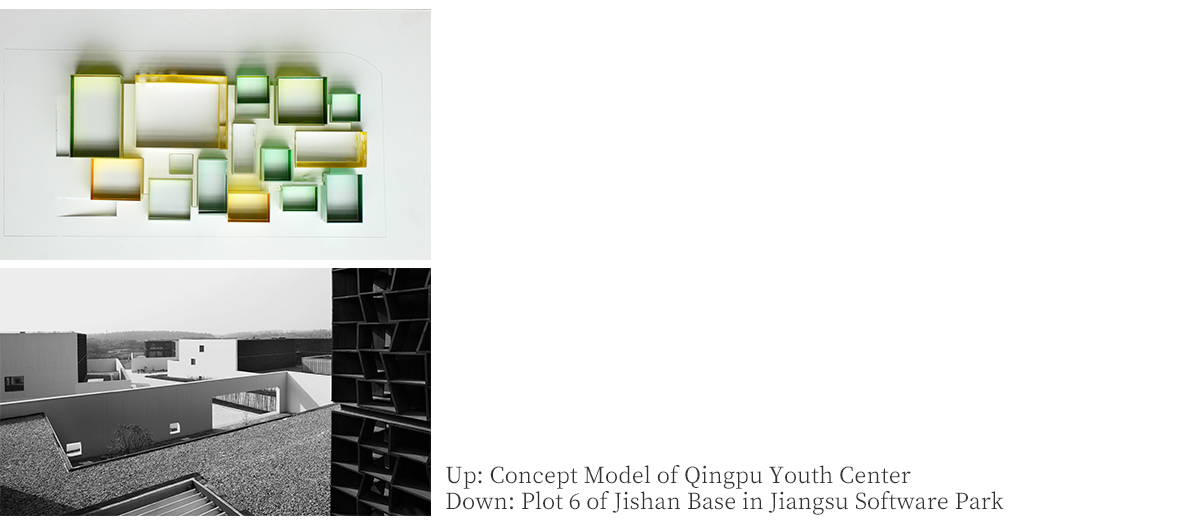

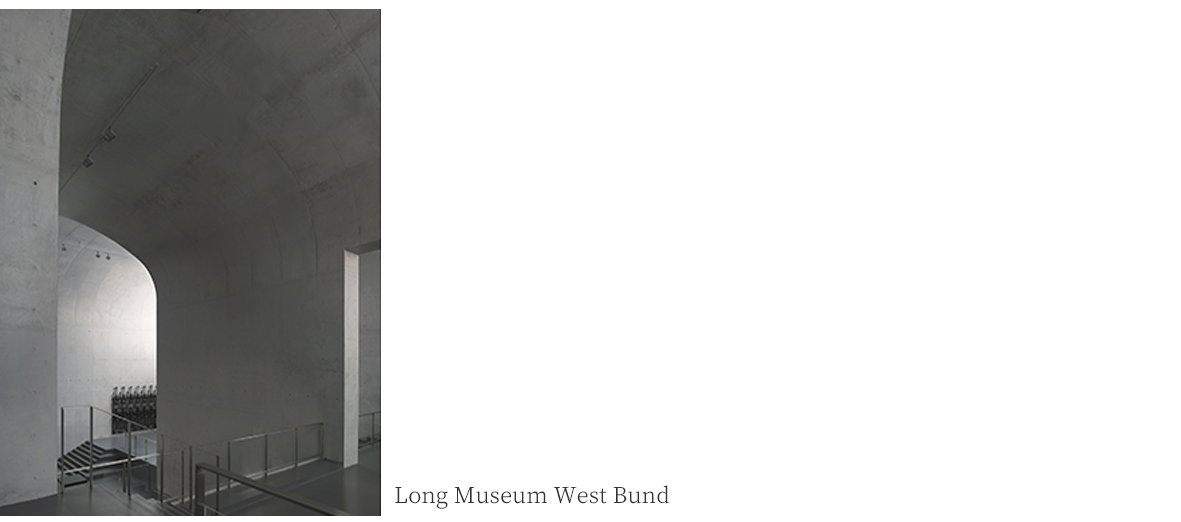

Once in an article, Liu Yichun accentuated the duplicity of objecthood. "The materiality of architecture indicates that the structure has special significance for its essential value in the concept of architecture. It is the skeleton that allows the architecture stand and be constructed as an object. Moreover, things themselves carry meanings. Hence, the structure also helps to constitute both the symbolic and cultural sides of architecture. " [4] The word 'structure' is used to remove the engineering feature of 'construction' and put more weight on the cultural aspect of it. Thus, structure and meaning became the two measures by which Deshaus emphasizes objecthood. They are the attributes they found in the coal hopper corridor reserved on the original site of Long Museum as well. This is a pure structure, completely complying with the mechanical limits of materials, frankly representing the connections, load relations and textures of materials. Meanwhile, it is also an articulate announcement, demonstrating pursuit of pure utility, technical efficiency and rational control in industrial manufacture. These qualities or virtues have transcended the utility of industrial production and become part of the values we agreed upon. It is because of these characteristics, the coal hoppers were reserved as a heritage, and the duplicate value it contains were transferred into the very core element of Long Museum --the umbrella units. When geometric relationship of space is taken as a principle ideal, architectural elements are often abstracted into pure geometric volumes or surfaces, while interior structure, material differences, equipment and pipelines are all overridden by solid-color painting. This approach is commonly applied in many of the early works of Deshaus. With this in mind, the umbrellas in Long Museum are so distinctive in that the exposed as-cast concrete truthfully tells the materiality of the structure and its making process. The visual features and operation logic of the material is manifest everywhere is Long Museum. Behind its concrete surface, the umbrella units have elaborated internal structures. Based on the previously built frame foundation, two concrete walls are erected on both sides of the original columns and beams, with plenty of void left in between for pipelines. The void extends sideward with the walls bending outwards on the top, producing more space for illumination, firefighting and air-conditioner pipelines, even for man walking through upright. The method of accommodating equipment and pipelines in a deliberately designed hollow structure reminds us of its name as "hollow stone" by Louis Kahn in his discussion of the serving and the served. Without doubt, this method makes it convenient to accommodate equipment and pipelines, but there's more to it. The important difference between providing a hollow space for pipelines and leaving them around or belying it with overcoating may not be the concern of convenience only. What divides them is also the architect's attitude towards equipment and pipelines: whether to give them respects they deserve and to provide them with a place they belong to, or to take them as drags and to disguise them with the simplest method. It doesn't matter if pipelines are visible or not. What it indicates is a deeper attitude towards common object, whether to respect the most insignificant things we meet in our life or not. This can deeply influence an architect's thoughts, as it can be demonstrated by Kahn's conversation with a brick. Seeking the essence of small things and figuring out a placement scheme in conformity to that essence, brings architects closer to the role of a creator somehow. According to a number of religious theories, the creator created not only the world, but also all the things with their corresponding positions in the world, and winded up the spring of the world mechanism. Reading an architecture, understanding the identity of everything, their positions and connections in the whole, resembles the reading of the entire world. Maybe this is one of the pivotal implications on the expressional level of tectonics that Frampton emphasized. [5]

Although all the constructional concerns in Long Museum are blocked to visitors' direct view, what's truly valuable has been built into architects' standpoints regardless of their absence on the very surface. With these standpoints, architects were able to attain a new approach and open a new area to show the charisma of architecture that once has been suppressed by the space paradigm. It is actually one of the supporting strengths for architectural art throughout the thousands-of-years history. On the contrary, the space paradigm is only a temporary exceptions deserving reflections and suspicions.

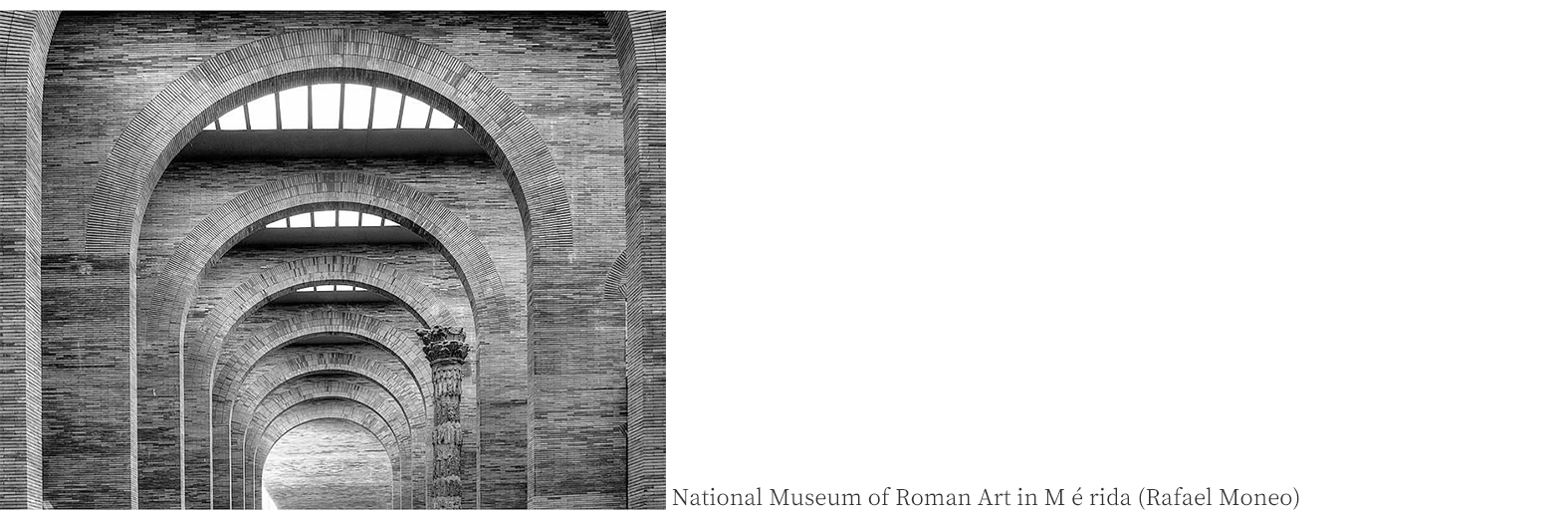

In Long Museum, the tectonic meaning of the umbrellas may be obscure for common visitors, but their genetic resemblance to vaults delivers a straightforward and robust meaningful reference. When designing this element, Liu Yichun admitted, they were simply concentrating on the supporting and coverage nature that an umbrella typically possesses, with no intention to shape the vault. But when the umbrella structure was transformed into successive surface walls, architects themselves were struck by the atmosphere it created. "The moment the big scale working model was merely half-finished, the word 'Rome' came to life." wrote Liu.[4] Rome was not built in one day. Likewise, it is rather effortful for contemporary architects to get mentally prepared to accept Roman glory and present it in their own works. We can see how difficult it might be simply by taking count the limited number of contemporary architectures that are qualified to present the antiquity of Roman architectures, among which Rafael Moneo's National Museum of Roman Art in Mérida is undoubtedly a masterpiece. Yet in China, apart from the arch windows sticking to the quasi classical facades and the domes symbolizing authority of government, Long Museum is probably the only work that enables us to bodily feel the charisma of the greatest architectural element coming from the Ancient Rome.

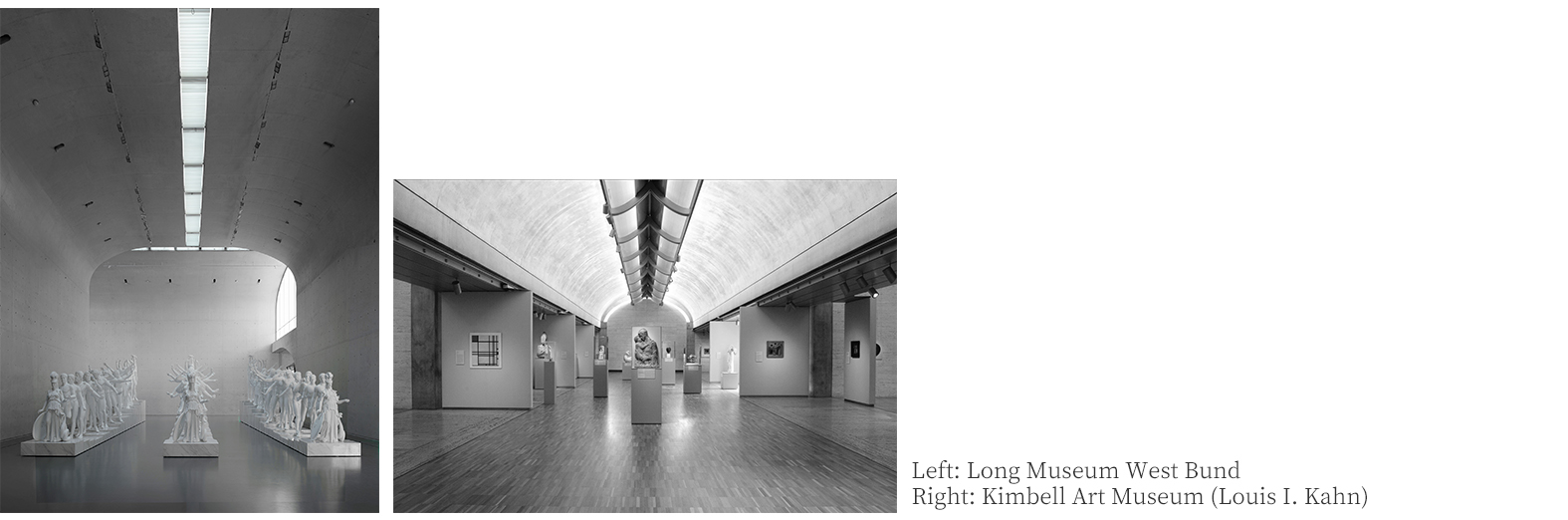

Long Museum is naturally associated with Louis Kahn's Kimbell Art Museum since they both are related to vault, although neither of them is made of real arches in terms of mechanical structure and neither of their shapes is a typical semicircle. Besides, they also share similarities in introducing daylight on the vaults and using concrete to build the vault. Still, their differences should be addressed. Kahn chose cycloid section to mitigate the height of semicircle vaults, so as to reducing the ceremonious atmosphere. While in Long Museum, the plan of the umbrella structure is of a bigger scale and often extends to two-story high, creating a much stronger monumentality. Another significant difference is related to Louis Kahn's concept of a room. In Kimbell, one segment of vault makes a well-defined room with no proper reason to interrupt. He wrote, "The vault resists division. Even if it is divided, the room is still the room. You can put it as the nature of the room enables itself to keep an integrated character." [6] Yet in Long Museum, the integrality of vault is clearly defied. Standing underneath the enormous umbrella structure, what people can feel is actually half a vault, and the intersection of the umbrellas breaks the disciplined order as it is in Kimbell, rendering a sense of consistent flow between different areas. One effect produced by this difference is that the sense of materiality of the umbrellas is highlighted. This is because in the room of Kimbell, a vault is a component of the whole room, and together with the floors, walls and columns, forms an integrated enclosure. What people perceive is a room covered by vaults. But once the concept of room lost its leading role, the integrality of vaults and other elements is reduced, thus gives more expressive freedom to the autonomy of the umbrellas. This is also related to the different use of daylight in Long Museum and Kimbell. In Long Museum, every umbrella is surrounded by daylight, and the slits that exposed directly emphasize the independence of the standing units.

The slits also remind us that in spite of the form of vault, the umbrella is obviously an uncommon cantilever structure that requires special attention. It is true that the vaults in Kimbell are not pure, for they don't deliver side thrusts to the ends of vaults, but the cultural impression of vaults seduces ordinary viewers to take it as a true vaults with both sides balanced and supported by each other. Even the daylight is prevented from intervening this comprehension by the installation of reflection boards. Yet this misunderstanding does not occur in Long Museum, for the architects make the structural property explicit to every visitor. Bachelard once wrote that the vaults' wrapping people signifies "a great law of human beings' dream of attaining intimacy". [7] The umbrella structure, standing alone and reaching out arms firmly, suggests us a resolute object which needs to give arduous efforts to bear the load of weight with its own strength and intensity without any assistance from peers in the process of creating a shelter of peace. It turned the intimate atmosphere typified in the Kimbell into a heavy one, and the human feeling is intensified. The umbrella of Long Museum manifests once again that both the things and the property of things are powerful measures to introduce and pass on meanings. Hence, it can be inferred that one of the major differences between Long Museum and Kimbell Art Museum is that the status of the umbrella structure in the entire architecture is higher in Long Museum than Kahn's vaults in Kimbell. Kahn's room is an entirety constituted by enclosure and the space defined within, while the objecthood of the umbrella structure in Long Museum transcends other factors. The comparison of course is not setting a competition between the qualities of these two works. It is only a way to explicate how Deshaus went deep into the potentiality of objecthood in Long Museum when it aimed at the ultimate goal of "attaining meaning".

At Studio-X, Deshaus interpreted "Objecthood" as "Been", due to its connection with phenomenology and especially Heidegger's theory apparently. From my point of view, perhaps "thing" would be a better interpretation. It will allow us to borrow a classic argument in Heidegger's "The Origin of the Work of Art" to discuss another characteristic of Long Museum, the monumentality of objects.

Although the theme of the essay is about art works, Heidegger initially discussed a more universal question: what is a thing? To start with, he denied three incorrect opinions. The first one regards a thing as an entity with accidental properties. The second one refers to the unity of a manifold of sensations. The third one regards it as a formed matter. The third opinion is the most fashionable in art theories. To artists, matters are simply raw materials and fields for form creation, only form itself is substantial. The aesthetic principles derived from it will certainly belittle the matter aspect. But Heidegger's argument is that "The thing that is the most accessible to us as well as the most genuine one is the use-object around us." Therefore, the fundamental characteristic of an object is the equipmental being with usefulness, values and meanings. The so-called mere thing is in fact "a tool deprived of instrumentality". [8] It is in accord with this theory that the fundamental means of existence for human beings is participatory practice. If all human activities involve meanings, then everything must be meaningful to humans, thus can be included into our life world. This point is also acknowledge by Deshaus, as mentioned earlier, they emphasized that "object itself inevitably has the characteristic of meaning." And we have discussed the meanings of the umbrella structures in Long Museum.

Whereas things with instrumentality are familiar to us in ordinary life, then why do we render them mystery and endow them dramatic monumentality? We need an explanation to help understand the monumentality of the umbrellas in Long Museum. In the later period of Heidegger's philosophy, we found a clue. Everything in the life world carries meanings, and is subjected to the framework of meaning of the life world, and in this world a thing is disclosed as a tool. But we need to understand that the framework of meaning is not unique and there can be infinitely many of them. In that case, things can be disclosed in an infinite variety of meanings or as quite different tools. They normally don't appear to be so because we discard the other possibilities as soon as we choose a specific framework of meaning. As a thing unveiled to be a tool in the framework we choose, the infinite possibilities of turning out to be other tools will evaporate. The infinite plenitude of things as bearers of meanings is referred to as the earthly character of things by Heidegger, and it is accessible to those who are able to understand this process and those who have truly given serious consideration to the essence of things. [8] When confronting infinity, it is spontaneous for us to revere. That is to say, even if facing the humblest thing, those who are philosophically sensitive will respect it with awe. Here derives the monumentality. The same goes in Kahn's conversation with the brick and Carlo Scarpa's exploration in the possibilities of details. Compared to the common reverence towards heroes, authorities and etc, the ontological monumentality of a thing is more fundamental and profound.

This may be the reason why we often perceive a mysterious feeling in architecture works of Kahn, Scarpa, Zumthor, and Kazuo Shinohara, who show special preference to things. The infinite plenitude of a thing can't be articulated or comprehend thoroughly, because it is veiled, and lies beyond the framework of meaning that is used for comprehending the world. And here comes the mystique. I think this can explain the lofty feeling one has standing under the umbrellas in Long Museum as well.

It is not certain that architects in Deshaus are influenced directly by Heidegger's theory, though their interest in phenomenology literature like <The Poetics of Space> is likely to be related to this. Yet we would love to infer so from their last two lines in the introduction of Studio-X Exhibition:

"To care about the immediacy of Objecthood and Situatedness of Architecture, to us, holds a positive value in our practices. After all, we humans still perpendicularly and directly put two feet on the earth. And that is why even the simplest gesture of support and shelter can create a sense of permanence.

But, is there any sense of permanence of architecture in the near future?" [1]

Perhaps not anything is of permanence, even the universe. But to human world, the infinite plenitude of the "earthy character" of things transcends time, space and what we understand or imagine. The infinite mystique consists the most profound permanence.

82-91, Qing Feng, <World Architecture>, 2014, 3.

/