Art of Memory: Architecture of the Deshaus (Da She)

Zou Hui

/

The origin of the Western labyrinth can be traced back to the mythological Daedalus’ labyrinth in Crete. In addition to the first labyrinth, Daedalus designed a dancing stage for Ariadne. In illustrating Vitruvius’ manuscript, Renaissance architects literally interpreted the foundation of theaters as a labyrinth, implying the theatrical order as the ultimate destination of architecture. During the Middle Ages, for many Christians, the labyrinth was a way to forge a symbolic pilgrimage to Jerusalem. In European Baroque gardens, finding one’s way in a labyrinth meant to become an honest man and the labyrinth was thus a map of virtues. In the late eighteenth century, when the Western Jesuits designed a "Western-like garden" for Emperor Qianlong in the Yuanming Yuan (literally, "Garden of Round Brightness"), they intentionally built a labyrinth at the entrance of the garden.

While meandering paths in Chinese gardens provoked a bewildering sense, the Western labyrinth in the Yuanming Yuan posed a counterpart to the Chinese traditional concept of labyrinth. The Jesuit garden began with the labyrinth and ended at an open-air stage made of illusionary perspective paintings. This theater bordered with a small Chinese garden named Lion Grove in the northeastern corner of the Changchun Yuan (literally, "Garden of Eternal Spring," as a part of the Yuanming Yuan). The Lion Grove in the Yuanming Yuan imitated the Lion Grove garden in Suzhou of the Jiangnan region, which was well known for a rockery-hill type labyrinth. Being fascinated with the original Lion Grove, Qianlong built two new Lion Groves, one of which was located in the Yuanming Yuan. The poetry on the Lion Grove in Suzhou from the Yuan to the Qing dynasties provides detailed references about how the Buddhist Chan philosophy was fused with the rockery labyrinth. Qianlong wrote a vast amount of poetry on the relationship between the original Lion Grove and his replicated Lion Groves. Through both his replications and writings, his respect to the history of a poetical environment was clearly expressed. Meanwhile, the Qing imperial archives conveys how much he enjoyed strolling in the Western labyrinth in the Yuanming Yuan, a thaumata built to produce wonder rather than to dominate nature.

On the Lion Grove in Suzhou, a Qing poem states:

The path of the Lion Grove turns at multiple levels, Need to remember the varied lions before climbing. In this sacred field I do not make any mistaken detour,

I am afraid to get lost and be growled at by the lions.

I have been to the Lion Grove multiple times,

Be familiar with the exquisite stances of the lions.

Walk through the lions’ bellies and cross over their backs, I climb straight up to the lions’ tops.My dear lions, I have not yet lost myself.

The meandering path went up, down, left and right; but the author did not feel perplexed in his strolling. He memorized the form of each rock and gained freedom through correct choices and this freedom in the labyrinth provided him with an ecstatic mood. The poem demonstrates that through the rational engagement of memory, the perplexities of a labyrinth can lead to great joy in spirituality. The mythical order of the labyrinth thus mirrors the cosmic order of the divine world.

The German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz had a close relationship with the Jesuits in China. In his books, he expressed the pride in Western metaphysics and argued that through demonstrations of geometry the nature of eternal truth could be perceived. He described Chinese philosophy as remaining content with a sort of "empirical geometry", which was different from the Western transcendental geometry. Both Leibniz and Matteo Ricci (Chinese name, Li Madou), a pioneering missionary in China, agreed that there was indeed something in Chinese philosophy that corresponded with Western metaphysics. Their discussions focused on the Neo-Confucian concept li (roughly in English, "reason"). Leibniz expounded the li as "the substance of things" and stated that from the unity of li and qi originated the five elements (gold, wood, water, fire, and earth) and physical forms. Because the li could be united with the qi, Leibniz thought that Chinese spirits, e.g. heaven or the spirits of mountains and rivers, were composed of the same substance as physical things and had a beginning and end along with the living world. Citing the Neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi's thoughts, Leibniz inferred that the li should have been conceived as embodied "spiritual substances" that were "clothed in subtle material bodies," like Angels of Christianity. On the one hand, the li was taken as the invisible law of the world; on the other hand, it was supposed to be composed of the same substance as physical things.

Geometry played an important role in the Western medieval art of memory, which was later introduced to China through the Jesuits' translations. In his Chinese book on the art of memory, Ricci (Li Madou) stated that to memorize was to find the place where images were stored in a strict order. The success of memorizing depends on the lifelike effects of images and well defined places. The place for memory is like a house where people actually live. Nevertheless, the place of memory is not a simple house but rather intends for infinitely approaching the transcendental truthful world. Through the building process of bizhen (close in on the real), something invisible in the world becomes conceivable in memory.

The Jesuits in China applied transcendental geometry in the experiments of perspective representation, which successfully drew the rational "concentration" of the Chinese mind. But the Jesuits did not find an effectual way to identify the metaphysical light within the Chinese context until they encountered the vision of jing (i.e. the bounded bright view of a garden scene) through creating a Western garden in the Yuanming Yuan. It is on the poetical ground of gardens that the Jesuits created the perspective jing of "brightness without shadow", which embodied the cultural fusion. The vision of jing, visualizing the spirit of a poetical habitat, can be identified with Leibniz's "angel incarnate", which shifted between the divine and material worlds. According to Chinese thought, the spiritual substance would rise to heaven after the disappearance of a poetical environment (e.g. a garden). The "angel incarnate" might be looking down from heaven and waiting for the opportunity to descend to earth. Is contemporary China ready for the angel's return?

Leibniz's discussions on the li in its revealed relationship to the angel incarnate and the Jesuits' perspective jing remind us of the poetical tradition of the Chinese built environment where view (jing) and emotion (qing) always fuse. Such a rational but compassionate approach is well demonstrated by two modern buildings, built in 1928. One is Mies' German Pavilion in Barcelona; another is the Leibniz's discussions on the li in its revealed relationship to the angel incarnate and the Jesuits' perspective jing remind us of the poetical tradition of the Chinese built environment where view (jing) and emotion (qing) always fuse. Such a rational but compassionate approach is well demonstrated by two modern buildings, built in 1928. One is Mies' German Pavilion in Barcelona; another is the analytical philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein's house in Vienna. Mies’ minimalist abstraction and Wittgenstein's conscientious measuring demonstrate the extreme rationalization of space creation. In both cases, the consciousness of humanity is not lost but rather developed through careful consideration of physical details. Their building boxes act as a singular container of poetical passion, which are distant from the homogeneous landscape of box buildings resulting from mass production.

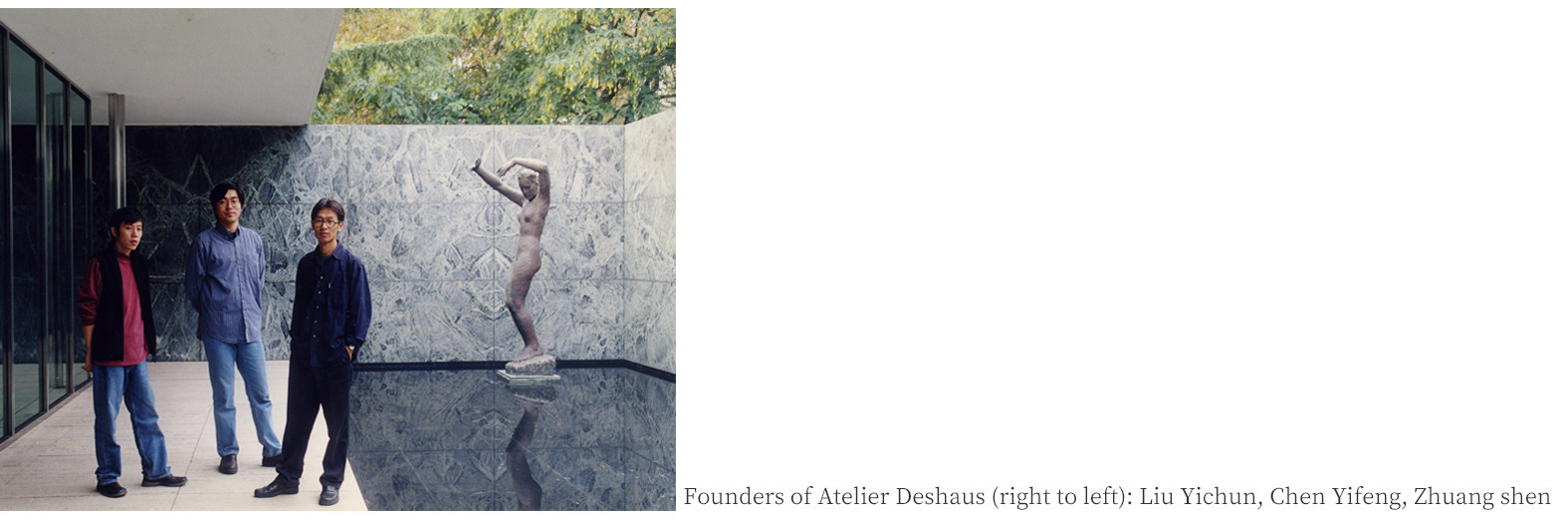

The three founders of the Deshaus firm completed their graduate studies in the 1990s at Tongji University where the history of architectural education was deeply intertwined with the Bauhaus influence. The name of the firm clearly demonstrates their critical reflection on the modern architectural history in China and their desire to return to the fundamental in architecture, namely the building as dwelling in the German philosopher Martin Heidegger's sense. For Heidegger, the common ground shared by building and thinking is dwelling, which presents historicity as the horizon of being and time.

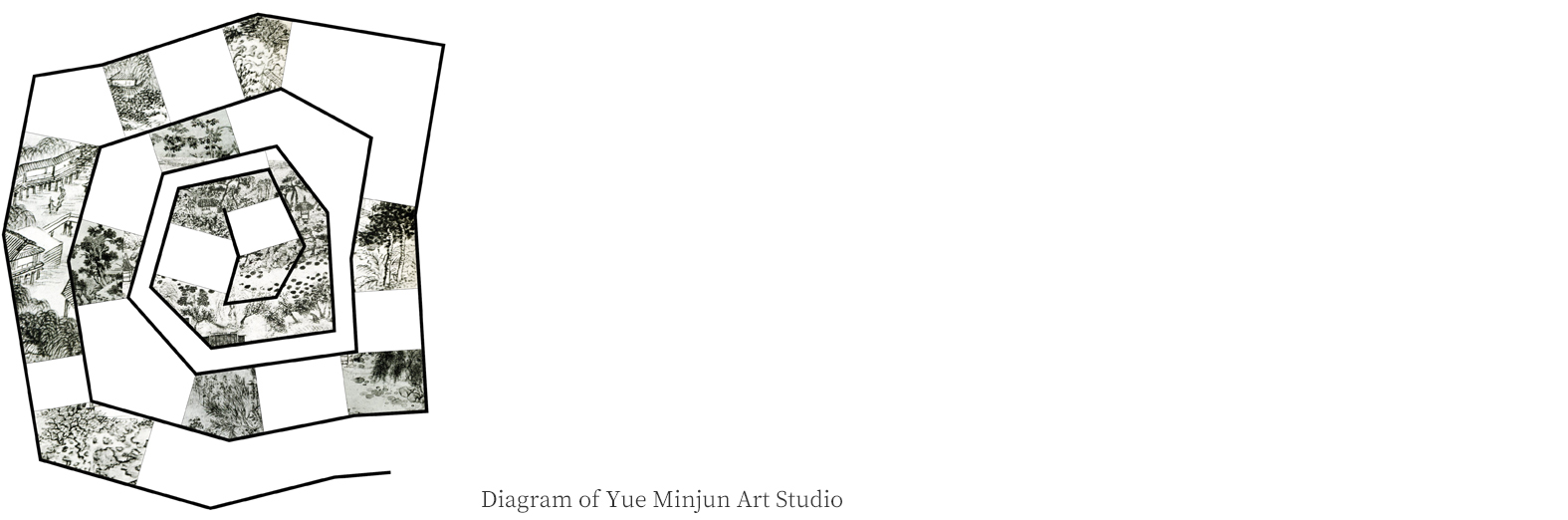

The architecture of the Deshaus seeks "a rational approach that is linked to a personal touch". Its rational and personalized attempt is different from the emotionless realism and narrow- minded manifestos in modern architecture and is closely related to its reproduction of the poetical tradition. Seeking the fusion of li and qing, the Deshaus endeavors to create the place for memory in each project. In the design of the Dongguan Institute of Technology (2004), they carefully studied the site and laid out three box-like teaching buildings, which enclosed the hilltop landscape at the center from three directions. Each box is a different shape, subtly fitting into the slope of the topography. The rational image of the boxes in contrast with the soft contour of the site and its surrounding landscapes helps establish the sense of learning order. Critically reflecting on the box image of modern architecture, the architects cautiously controlled the building scale in the section designs. The boxes hold a gesture of either anchoring into the ground or floating above the ground, leaving the view towards the horizon of land unobstructed. The design intentionally breaks through the mass of the boxes with varied voids, e.g. courtyards, arcades and terraces, so that "the pressure on the surroundings asserted by the building is relieved". These voids also provide viewing opportunities from inside out towards the landscape in the distance. Through the interweaving of multiple viewing, a memory of the original landscape is established.

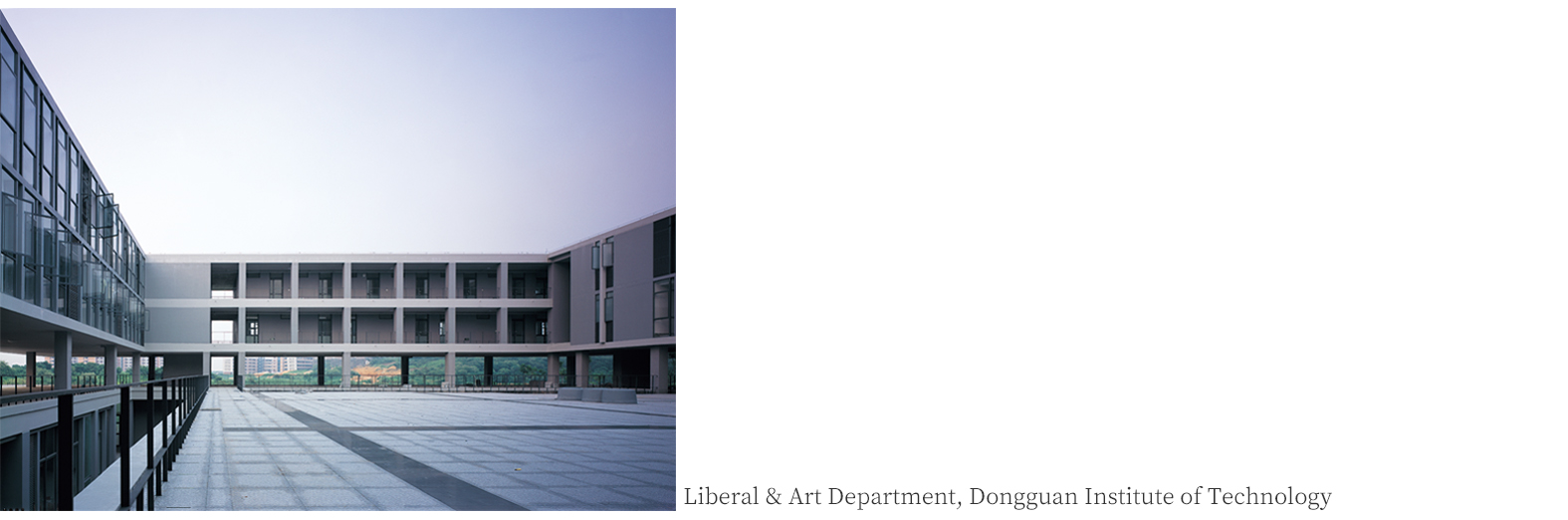

The careful considerations of the opportunities for viewing in and viewing out on a specific site is well demonstrated in the design of the Building for the Association of Private Enterprises in Qingpu (2005) where the Miesian-like crystal cube generates compassionate perceptions to the surroundings. The ground floor is opened up to let the internal garden and the external landscapes flow into each other. The architect presents the idea of boundary, which is composed of double layers of curtain walls. The outer-layer curtain wall is made of transparent glass. Between the outer and inner curtain walls is a green corridor of bamboos, which acts as the buffer zone between privacy and publicity. The transparent and reflecting surfaces of the building reduce the sense of intrusion into the context. The view of real bamboo between the curtain walls mix with the reflected images of trees on the wall surfaces and thus creates a collage of reality and illusion. The effects of collage well confirm the architect's idea that "the building can softly fuse into the environment". The method of presenting exterior landscapes while enclosing an interior garden through glass curtain walls can be traced back to Mies' another building of 1928, the Tugendhat House. The female client of the house passionately followed Heidegger's lectures. Reflecting on Mies' glass houses, the compassionate box of the Deshaus endeavors to un-conceal the dwelling in Heidegger's sense, which is not only to construct but also to cherish and care for the earth, specifically to "cultivate the vine" (quote from Heidegger) as, for example, the design of Mr. Yue's Artist Studio (2008).

The art of memory sought by the Deshaus is boldly demonstrated in the design of the Zhu's Clubhouse in Qingpu (2007). Two pristine solid boxes on the second floor enclose respectively the replicas of a traditional courtyard house and a classic garden of the Jiangnan region. The replica of the classic garden imitates the Lion Grove in Suzhou. The first floor is enclosed with glass walls into the Miesian-like free flowing spaces whose dynamic and transparent image forms a sharp contrast with the quiet and opaque boxes on the second floor. The shift from the experience of the Miesian spaces into the mystical traditional house and garden is a drama, which recalls the ecstatic encounter of Western and Chinese labyrinths in the Yuanming Yuan. The radical gesture of wrapping tradition with modernity is not to hide the tradition but rather to retrieve the inherent magic order of Chinese architecture. This wrapping gesture is humble and sensitive, full of respect to history, and enlivens the history as the "theater of memory" designed by Giulio Camillo in sixteenth-century Venice. Such an approach of historical preservation is poetical and far more effectual in engaging history than taking the past as an outdated or nostalgic object for museum-like protection. For Heidegger, the true building as dwelling should "preserve" the fourfold of the world: earth, sky, divinities and mortals. Through gathering the fourfold, genuine buildings give form to dwelling in its essence. From the phenomenological theory of dwelling, we might get a better understanding of the name, Des Haus.

Heidegger used four verbs to explicate the preservation of the fourfold in dwelling: save the earth; receive the sky; await the divinities; and initiate mortals. The fourfold is gathered through a site of spaces whose boundaries initiate the horizon of beings. The meaning of Heidegger’s gathering site is close to Plato’s chora, namely space, the receptacle of becoming. Plato defined this receptacle beyond the intelligible and visible worlds and compared it to the mother. In the design of the Xiayu Kindergarten in Qingpu (2004), the architect carefully studied the site and found that soft curved boundaries best laid out the plan. The design idea is about the “container” full of sunshine where young lives grow like fruit trees. These soft curved boundaries enclose wonderful spaces for the growth of children and initiate their colorful dreams when they nap as little floating clouds under the blue sky on the second floor.

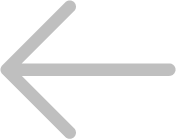

The labyrinth as the myth of Daedalus and its phenomenological meanings were deeply explored by architectural historian Alberto Pérez-Gómez in the 1980s. According to Vitruvius, the meaning and beauty of architecture were dependent upon rational order, but Pérez-Gómez argues that Vitruvius failed to deal with rituals as the meaning of cosmic place. He points out that Western architectural theories tend to reveal the idea of labyrinth as order, i.e. the Ariadne's thread, but in fact the idea of labyrinth is more related to ritual, like the dancing place designed by Deadalus for Ariadne. In his new book Built upon Love, Pérez-Gómez further states that architectural rationality should be the capacity to interpret a situation and propose appropriate answers that are adequate to such a situation, and reaching an appropriate understanding happens in dialogue through a profound comprehension of history and culture. I think his discussion of "appropriateness" resonates with the Chinese traditional concept of "pertinent emotion and reason" (he qing he li). From this perspective, we begin to understand the importance of the dialogue about labyrinth between the architect and his client in the design process of Mr. Yue's Artist Studio.

The photo of the three Deshaus founders standing in the backyard of Mies' German Pavilion touches me. They belong to the new generation of architects who were educated in China and strive for the revival of poetical habitats in contemporary China through the unprecedented open mind. They reflect on the fluctuations of ideologies in Chinese modern history and are determined to seek fundamental understandings of architectural truth. In the arduous process of approaching truth, the Deshaus does not follow the fashionable trends in global architecture which present no historicity; rather, they begin by contemplating on who they are and where they are. They sharply observe what is missing in the history of Chinese modern architecture and search for the new understanding of reason (li) which does not cut off its relationship with the traditional philia of poetics and ethics (qing). Such an ambition requires the engagement in memory through art from a cross-cultural perspective, like Ricci's "art of memory". Mies' architecture is usually taken as the representative of modern abstraction movement, but in fact his glass boxes always occasion a metaphorical memory of Western classic tradition. In the preliminary design of the German Pavilion, he originally set up three statues on the ground, respectively in the front pool, the roofed space and the back pool. Finally, he got rid of the first two statues and only preserved the third one. The statue, entitled Morning, presents as the secret destination of the journey in the labyrinth of flowing spaces. Scholarship has compared this journey to that at the Greek Temple. For the three principals of the Deshaus, I wonder if the same statue in their photo hints at Leibniz's angel incarnate.

/

Biography

Zou Hui, Art of Memory: Architecture of the Deshaus (Da She), T+A, 2009/02

Dr. Hui Zou teaches at the School of Architecture, University of Florida, USA.